Today translator Andrea Reece talks to World Kid Lit co-editor Claire Storey about her work translating a series of award-winning non-fiction Spanish books focusing on Science, Technology, Engineering and Maths (STEM)…

World Kid Lit: Hello Andrea and welcome to World Kid Lit. We’re excited to find out more about your work. Could you start off by giving us a quick introduction, what are your language combinations and how did you start out work as a translator?

Andrea Reece: Hello. Thanks so much for having me. I translate from French and Spanish and have been a translator since 2010. I started when a friend of a friend contacted me one evening to ask me if I was interested in translating city and museum audioguides for a French media development company. I enjoyed doing that for a number of years and, in the meantime, also completed an MA in Literary Translation at Exeter University. Returning to studying twenty-five years after my undergraduate degree was an uphill struggle but also very rewarding.

WKL: You have been working on a series of STEM picture books by Spanish creators Sheddad Kaid-Salah Ferrón and Eduard Altarriba for Button Books (also available in the USA). Could you tell a little bit about the books?

AR: Since 2018, I have translated the texts for four science illustration-led books and each process has been very different. I was commissioned to translate the first two by the lovely team at Button Books, whereas the third and fourth, I worked directly with the equally wonderful Sheddad – the texts’ author – before the books were acquired by GMC.

Sheddad studied physics and pharmacy and is clearly passionate about science and keen to share his knowledge and the human stories behind the development of science. His texts were written for his own young son to read, and, as I discovered throughout the translation process, the fun approach and the well-matched lively illustrations by Eduard also make them great for parents to read with younger children.

WKL: Some of the titles include My First Book of Microbes, and My First Book of Electromagnetism. Do you have a scientific background, or did you have to do lots of research for each of these topics?

AR: I’m not sure a low graded Biology O-level from the 1980s counts as scientific background, so my answer to the first part of your question is no! But I have been working for many years with a German scientist proofreading English biotechnology texts translated from German. So this and my humble O-level gave me some knowledge that helped with the translation of the microbes book, at least.

It is one of my regrets that I couldn’t study physics at school because it didn’t fit in with my other subjects, so I relied on lots of outside help for My First Book of Electromagnetism (notably a friend who is a professor of systems engineering at Southampton University). For My First Book of Relativity, I found and read lots of children’s books on the subject in my local library, and, at the time of translating, I can claim to have understood the thinking behind relativity. Of course, I’ve forgotten it now.

For My First Book of the Cosmos and My First Book of Microbes, I relied on online resources, particularly websites like BBC bite-sized, and I also found various pedagogical videos on YouTube, which helped with a visual understanding of certain areas.

In addition, I had long email exchanges with Sheddad for the first two books, mostly in Spanish as he reads but doesn’t necessarily speak English. All my translations, as far as I am aware, were also subject to a technical read, organised by the project editors at Button Books. For My First Book of Relativity, for example, I was involved in a to-and-fro, translating the questions from the technical consultant into Spanish for Sheddad, and Sheddad’s answers back into English for the consultant to approve.

For the Microbes and Electromagnetism books, where the translations were directly commissioned by the authors, Sheddad and I worked very closely together, doing a detailed final edit over the phone. As the Spanish and English versions were published simultaneously, there were a couple of occasions when my comments brought about changes in the Spanish original, either to slightly re-word text or correct minor errors.

These being the first children’s books I’ve worked on, I learnt during the process how integral the images are to the story being told. And how, rather than being just illustrations of the text, the images actually tell part of the story or broaden the textual explanations. This may seem obvious to many people, but the process made me realise just how much of a ‘word’ person I am, always trying to find the meaning in words without necessarily making the most of visual clues. I was totally absorbed by Eduard’s illustrations: they show how pictures are worth a thousand words.

WKL: How did your translation process for these books differ from other projects? The books are so engaging, with bright colours, diagrams and different fonts. How did you ensure the correct text ends up in the correct place?

AR: With book translations, I always ask the project editor or person who has commissioned the translation to supply me with the text in Word, organised in a way that will make it easy for the graphic designer to flow the English translation into the layout.

I then translate directly into this Word document on my laptop screen connected to a second, larger screen where I can simultaneously view the PDF of the original book (if I don’t have the original book in paper form, which would be my preference but obviously wasn’t possible here as the Spanish book hadn’t yet been published). That way, I can view the images to help me understand the text and the general layout, i.e., how everything fits together, the space available, as you say. I don’t have to adjust font sizes as that is done once the translation is delivered but I do keep an eye on the space available on the page for sections of text and try to ensure the English version isn’t longer than the original.

With these books, I delivered my translation alongside the Spanish text to help the graphic designer insert it into the right places.

So to answer your question, my process differs from other book translations in that, because there are visuals, I am more likely to continue referring back to the original throughout all drafts of the translation to check the text matches the images. Whereas for books that are solely text, from about draft 2 I tend to work on and edit my English version without reference to the original, before going back to the original version just before delivery to check I haven’t missed anything out or misinterpreted something.

WKL: Can you tell us about a particularly fun challenge and how you came up with a solution?

AR: The whole process for all the books was fun and challenging. It was such an exhilarating experience to dive into Sheddad’s textual worlds, read the stories and learn about the science behind them and to be accompanied by Eduard’s very vivid and playful drawings, which often made me laugh.

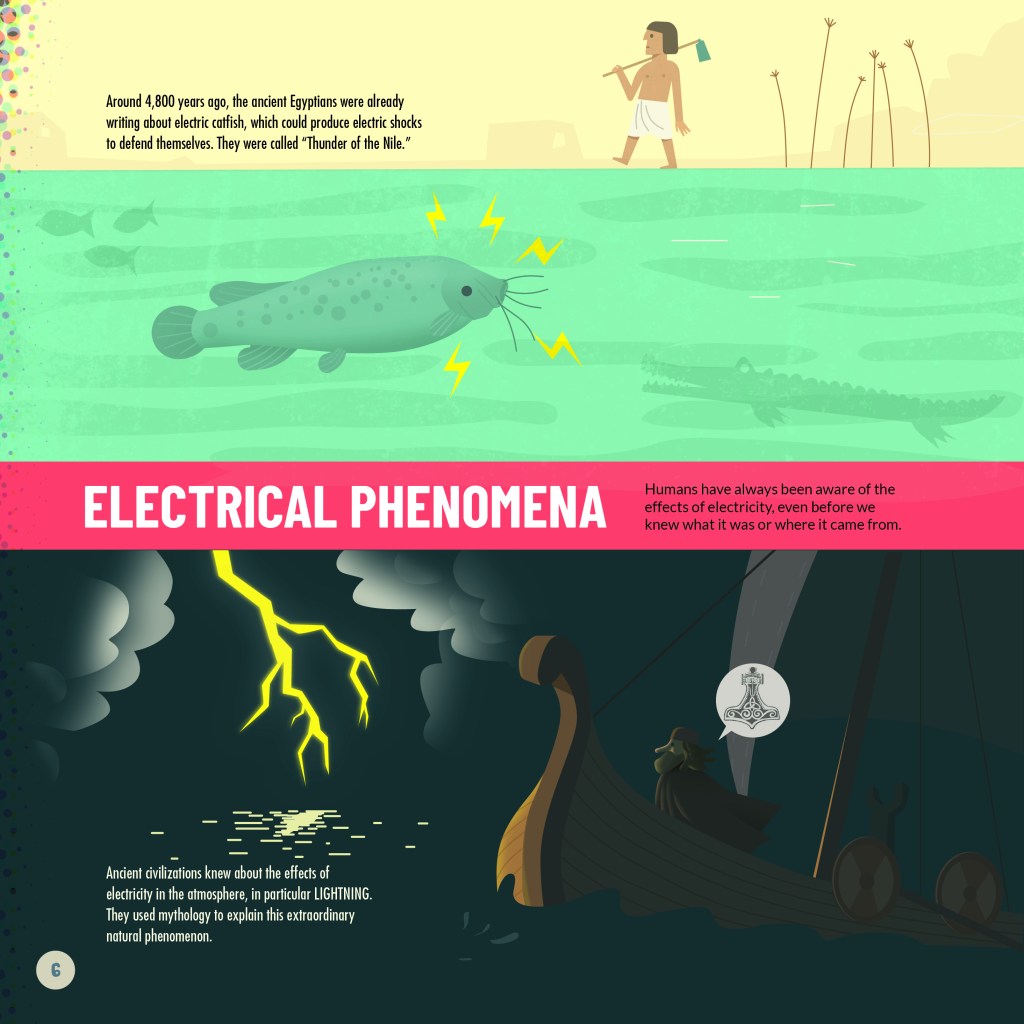

A couple of issues arose in the translation of My First Book of Electromagnetism which meant that the images didn’t necessarily work when the text was translated into English.

The first was an image of an electric eel in the introduction to electricity. The text claimed that the Ancient Egyptians referred to the eel as Trueno del Nilo (Thunder of the Nile). When I researched this in English, I found that Thunder of the Nile referred to an electric catfish rather than an eel. I was worrying about how I would get round this issue with words, so I spoke to Sheddad, who checked and found that the Spanish also referred to a catfish, not an eel. Eduard simply drew a replacement image. Easy to do when the book hasn’t yet been published!

The second challenge was another vocabulary/image one. The Spanish language has two different words for battery: pila (primary, non-rechargeable battery), and batería (secondary battery, or accumulator, which is rechargeable). Hence, the book has two images. Although English does have the terminology to differentiate the two, we more often than not use the generic term ‘battery’ for both meanings. The question here was how much detail we needed to go into for the English version. In conversation with Sheddad, we decided that using ‘batteries’ for both would serve the intended purpose and allow us to keep the two drawings.

In My First Book of Microbes, there is an example of a vocabulary and space challenge in a small insert. The Spanish version explains that the word vaccine comes from the word ‘vaca’ (‘cow’ in Spanish), and is accompanied by an image of a cow’s face. This page also tells us about cowpox so it would be a shame to lose the image but what to do? In the end, research revealed that the Latin for ‘cow’ is ‘vacca’, allowing us to retain the reference. Phew! However, my first draft – The word “vaccine” comes from “vacca” which is Latin for cow” – was 25 characters longer than the original so needed reducing to fit in.

WKL: You also have two new translations, again created by Eduard Altarriba: What is War? and Migrants. Could you introduce them to us?

AR: Yes, they came out in April in the UK and were entirely the work of Eduard Altarriba and his design studio Alababalá. These are two books that clearly explain the whys, whats and hows of war and migration and give specific historical and contemporary examples. The tone is neutral and explains, in a balanced way, the potential reasons for conflict and divisive issues such as xenophobia.

As always, Eduard’s accompanying cartoon drawings showcase his incredible ability to portray emotions with a couple of lines on a face that tell a story as clearly as the words do.

WKL: Have these books been different to work on, despite being created by the same creator? Have you approached your translations differently?

AR: Button Books purchased What is War? and Migrants from Eduard’s back catalogue and commissioned me to translate them. From my point of view, they were easier to translate as they required less research. History and geopolitics are two areas I have been interested in for a long time, and I already have a published translation written by a Rohingya refugee (First, They Erased Our Name by Habiburahman and Sophie Ansel, Scribe 2019) so these books felt like a continuation of previous work and research/reading I had done.

As the original Spanish books were published in 2017, some of the statistics needed updating but that fell to the valiant project editor, rather than me. Well done, Tom! In What is War?, there is a section about the war in Ukraine, including a map of occupied territories, which the editor struggled to keep up to date. Hopefully, before long it will look very different.

Prior to publication, these books were read by expert children’s readers to ensure they used appropriate language for the target age group.

Being relatively new to children’s book translation, I learnt a lot by going through the edits and seeing which individual terms had been changed and how the wording, in some cases, had been altered.

WKL: And finally, when can we expect to see these books hitting the shelves, both in the UK and the US?

AR: What is War? and Migrants will be published in the US in August and September, respectively. And another book of Eduard’s I have translated, entitled My World Economics, will be out in the UK in October and the US in Spring 2024.

WKL: Thank you so much for sharing these books with us today.

Awards and acknowledgments for the My First Book series

My First Book of Microbes

- AAAS/Subaru SB&F Prize for Excellence in Science Books 2023 – Longlisted

- British Book Design & Production Awards 2022 – Shortlisted (Finalist)

My First Book of the Cosmos

- British Book Design & Production Awards 2021 – Educational Books Category – Shortlisted

My First Book of Quantum Physics (translation for this book completed in arrangement with Alababalà)

- Junior Design Award 2018 – Best Designed/ Illustrated Book for Children – Shortlisted

- British Book Design & Production Awards 2018 – Educational Books Category – Winner

- AAAS/Subaru SB&F Prize for Excellence in Science Books 2018 – Longlisted

Meet Andrea Reece

One ‘translation’ issue I always had back when I lived in Spain was my lack of second surname, particularly when it came to filling in forms. Officials don’t like an empty box! Spanish people were amazed to find that in my culture, the woman’s surname is traditionally lost upon marriage. In Spain, husband and wife retain their own surnames from the maternal and paternal side of their respective families. So for my second surname, I used my mother’s maiden name – Mundy – when I could. It had effectively been lost to our family after my mum and her sister married and my grandparents died, so I also decided to revive it in the name of my website: www.mundytranslationbureau.com. This was a good excuse to adopt as a logo a wonderful tiny wooden bureau that my talented grandpa had carved in his garden shed.