Today, translator Siân Valvis talks to Mark Sutcliffe from Fontanka, a publishing house that brings Russian and East European culture to the world, releasing books on subjects that range from folk stories for children to historical studies and works on art and architecture as well as contemporary culture.

Siân Valvis: Hello Mark and welcome to the World Kid Lit blog! We are very happy to have you.

Mark Suttcliffe: Thank you, it’s lovely of you to invite me!

SV: Could you start by introducing us to your publishing house. Where are you based and how did you get to where you are today?

MS: Fontanka has a partial presence on the top floor of Pushkin House in Bloomsbury Square in London – the cultural centre that focuses on Russia and Central and Eastern Europe. Partial because the top floor is really the home of the Russian Language Centre, run by my colleague and publishing partner Frank Althaus. Fontanka meetings take place there but otherwise we work at a distance – Frank from Pushkin House and I from North Yorkshire. Our book launches tend to happen at Pushkin House too. We’re a small team but work with superb designers, translators and editors. Thames and Hudson distribute our books.

How did we get here? Good question! Much more by chance than design, I think. Frank and I have worked together for over 20 years, initially as translators and editors of books published by others, and then, after we formed Fontanka in the early 2000s, on our own projects. For both of us, I think, Fontanka has been a wonderful opportunity to work with authors, translators, designers and illustrators, embarking each time on a new collaborative adventure. We see books for children as an important part of our current thinking, and we’re looking beyond our more established boundaries to encompass ideas from other Slavic countries.

SV: I know what you mean—children’s literature in translation offers such a valuable insight into other cultures. What other genres do you specialise in and why?

MS: We have always focused on books originating from or about Russia and Eastern Europe. We’ve both studied and worked in that part of the world. I first found myself living and working in Leningrad in the early 1990s while Frank was in Moscow – so our involvement covers the whole post-Soviet period. Our books include publications for museums and exhibitions, and we had a longstanding publishing relationship with the Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg. More recently we have published a few books for children, primarily in the age range 3-11, drawing on the rich Slavic tradition of folk tales and inspired by illustrated books from Eastern Europe.

SV: What has been your experience in trying to find children’s books for your list from around the world?

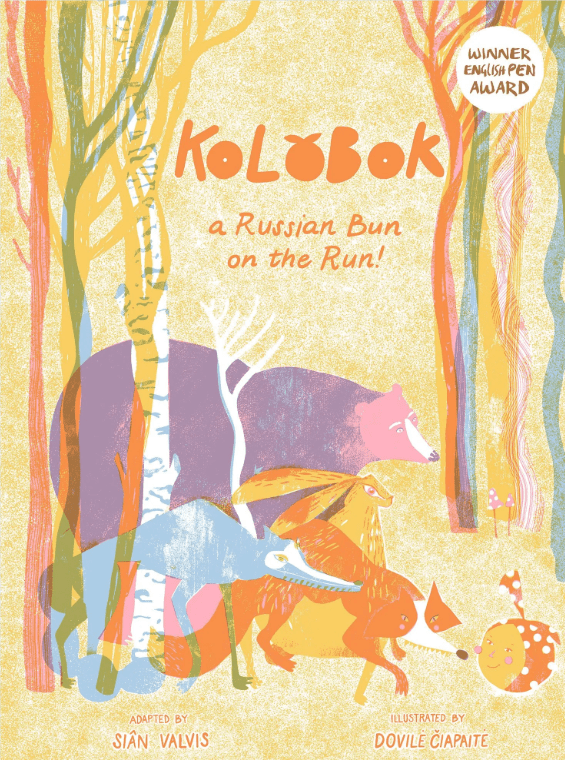

MS: There is such a wealth of children’s stories from Central and Eastern Europe, and this is something we very much want to focus on. When you, Siân, came to us with the idea for Kolobok, it was clear that this story of a little bun that escapes the frying pan and heads off to seek adventure echoed our own Gingerbread Man story – but in your hands the translation was so evocative of the Slavic tradition it came from, and so charmingly done, it managed to be both familiar and entirely original at the same time. This, I think, is the challenge: to find stories that are rooted in a distinctive culture that gives them originality and colour, but at the same time are just wonderful stories that in the right hands become wonderful translations and appeal to children wherever they might come across them. We are the least proactive of publishers, in that we tend to wait for people to come to us with ideas. But once we have agreed on a title, we put everything else on hold and go into another gear, working closely with our translator/illustrator/designer/editor – and that close collaboration, where everyone feels energised by a project, is the alchemy that produces a great book.

The challenge is always the funding. In the baldest terms, it’s really hard to make it work without some form of grant or sponsorship. There are organisations, like PEN Translates (which you were awarded for Kolobok), which can help, but there’s another problem that small publishers face: although we are well placed to identify books less represented in English translation, we often just don’t have the resources to do them. Since 2022, Frank and I have been discussing several books in translation that we would love to see in English but haven’t yet managed to fund.

SV: How do you pick your projects? When you are covering languages which you may or may not read, how do you go about finding people who can advise you on a certain book?

MS: As mentioned, we are not proactive, we tend to wait for books to come to us. With Kolobok we were brought together by the great translator and teacher Robert Chandler. The editing process is always collaborative and even more so when it comes to literary translations. For our children’s books, I think the best advisers are, of course, children. ‘Road testing’ a story with its target audience is crucial and the genuine, unmediated feedback received is very useful!

SV: I particularly love ‘Why the Bear has no Tail’ – how did you come across this collection?

MS: That’s so nice of you to say. I originally worked for the publisher Edward Booth-Clibborn who perhaps did more than anyone to champion the work of book designers; his books were always superbly designed and Fontanka has been lucky to work with some incredible designers like John Morgan, Christoph Stolberg – who designed Why the Bear – and Bureau Bureau. Bear was indeed a wonderful discovery. We were approached by Natalia Murray, curator at the Courtauld Institute, who had been alerted to the project by the researcher and now art and design historian Louise Hardiman. Through her research into the artistic community of Abramtsevo, Louise had discovered the drawings by Polenova, along with an English translation of the folk tales (made but never published a hundred years ago), in the bottom of a drawer in an Oxfordshire house owned by the descendent of the translator. Polenova’s drawings had of course been published several times, but what made the project so fascinating was this unpublished translation by Netta Peacock, who travelled round Russia in the late nineteenth century collecting traditional tales, and who knew Polenova. Her translation really brought the stories and the illustrations to life. Working on this with Louise, with the assistance of Peacock’s descendent, made me appreciate the timelessness of stories that may have originated in the oral tradition and could still appeal to children generations after they were written down. When we published Bear, my children were the right age to appreciate them and I never tired of reading them to them. We subsequently published a second book of folk tales with Polenova’s illustrations, The Story of Synko-Filipko and Other Russian Folk Tales, this time translated by Louise Hardiman, and as a result of the collaboration we came to know Natalia Polenova, the great-niece of Elena, who runs the Polenovo Estate-Museum.

SV: “Sometimes we need the oldest tales to remind us how to relish stories.” You have quite a few folktales in your catalogue—what do you think drew you to traditional tales in particular, as opposed to contemporary stories for children?

MS: I like that quotation. I think there is a very deep well of stories that connect us – who was it who said that there are only two types of story, someone leaving on a journey or someone arriving unexpectedly? – and whether or not that is true there is something about the power of folk tales to cross borders, to be both personal and universal, and to speak to us through the generations. We love contemporary stories for children too. Kolobok is drawn from a traditional source but it feels contemporary in the way it has been adapted, designed and illustrated. Illustration plays such a key part in these books. Dovile Ciapaite created the wonderful illustrations for Kolobok, for which she was shortlisted for the Klaus Flugge illustration prize. We feel very lucky that she has agreed to re-join the team for The Magic Ring.

SV: Yes, I’m very excited about this project, it’s been really lovely to watch it take shape! Can you tell us any more about other upcoming projects?

MS: We too are delighted to be working together again! Before you came to us with The Magic Ring, I knew nothing about the dialects of Northern Russia, and you have found a wonderfully rich and creative approach to it. Perhaps, like the other books, it is a reminder that language and cultural traditions are to be valued not just for their ability to cross borders of time and place but for their rootedness in what is local, in the communities whose stories outlast regimes and rulers.

Another book for children that we’re hoping to publish this year is by the artist Alexander Voitsekhovsky, whose illustrations we published in A Whale off the Coast of Norway and Other Encounters. Alexander has a truly unique perspective on the world, which hopefully his new creation – a philosopher kangaroo – may share.

SV: And lastly, do you have any words for readers, translators, librarians, booksellers? Are there opportunities for submission?

MS: Only that we feel nothing but the greatest admiration and respect for readers, translators, librarians and booksellers! We salute you all for keeping the magic of books alive. And yes, we really appreciate ideas for new titles – submissions are most easily done through our website.

SV: Thanks so much, Mark!

MS: Thank you Siân!

Siân Valvis is a British literary translator. Based in Europe and Brazil, she translates from Russian, French, Greek, and Portuguese. She has an MA in Translating and Interpreting from Bath University, and enjoys translating children’s literature – particularly folktales and fairytales.