by Amanda Bird

The authors, illustrators, and translators of the books below represent four continents and at least four languages. Such diversity seems particularly appropriate to these stories, where imagination and perspective bridge divides.

The joy of story is perhaps the most valuable gift any book can offer. But reading also—often subconsciously—opens a window onto our selves. Stories and imaginative play are means by which children process real life. In Out of the Blue and Goodnight, Commander, the protagonists forge imaginary friendships that would constitute uncommon bonds in real life—one with an enemy soldier and one with a wild creature. But such stories have the potential to cultivate real-life receptiveness to individuals different from or at odds with us.

Though these titles were selected with the theme of disability in mind, so deft is its handling that I almost overlooked it in writing the reviews. But it bears mentioning, if only because the authors weave it so seamlessly into the narratives. We are reminded that we all need—and can offer—the common gift of friendship. In Goodnight, Commander one cannot bypass the fact that the brutal injustice of war is to blame for the protagonist’s loss of his leg. But within the story a lack shared by supposed enemies occasions empathy and understanding.

One does not have to interpret Out of the Blue as a book about neurodiversity. But the sort of preference for order displayed by the boy is common in certain types of neurodivergence. His ability to incorporate friendship and change into his life testifies to his adaptability, despite initial appearances. And while the visual impairment of brother Mateo in Lucky Me no doubt imposes challenges on both him and his family, from the perspective of the narrator Bruno, everyone is a winner.

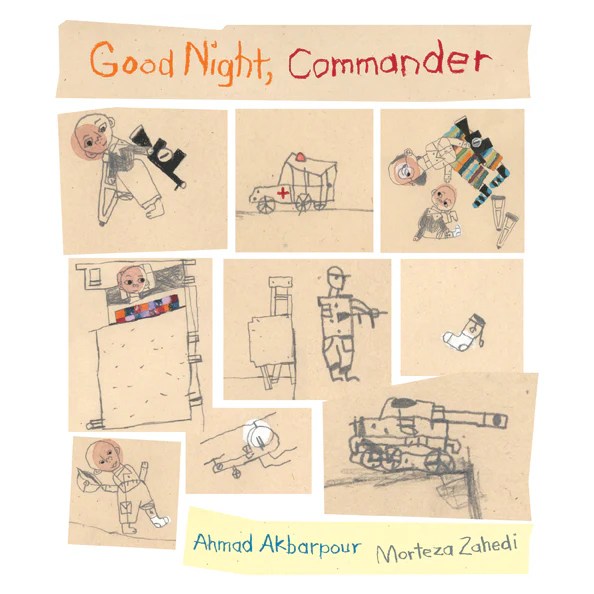

Good Night Commander

Written by Ahmad Akbarpour

Illustrated by Morteza Zahedi

Translated from Farsi by Shadi Eskandani and Helen Mixter

Published by Groundwood Books/House of Anansi, Canada (2010)

In his author’s introduction, Akbarpour describes the tragic civilian cost of the 1980–88 Iran-Iraq war. He reminds us that while such conflicts may go largely unnoticed by the outside world, the factors that fuel them are multinational and many faceted.

We first encounter the protagonist playing soldiers in his room. When his father urges him to remove his prosthesis while at home to prevent damage to it or injury to himself, the boy thinks, “How can I fight on one leg?”

Extended family come for dinner and then leave to meet the boy’s new stepmother. The little commander returns to his war games, intent on avenging his mother. But oddly enough, he meets a similarly one-legged enemy bent on the same mission. The two soldiers first threaten each other with guns. But then the commander suggests his enemy try on his prosthesis, then offers to let him borrow it for the night. When the enemy soldier runs off to show his mom, our protagonist looks to his mother’s photograph and hears it say, “I’m proud of you.”

Like the illustrators of the other two books featured here, Zahedi employs line drawings augmented by a limited color palette. He mimics the two-dimensional perspective common to children’s drawings, displaying the most prominent details of every item, regardless of whether these would be visible from the angle of the viewer.

Akbarpour’s training in psychology shows through in this layered exploration of the devastation of war and the healing power of imagination, generosity, and forgiveness. His other works for young people include the translated title That Night’s Train (Groundwood Books/House of Anansi, 2012), which also features a motherless child.

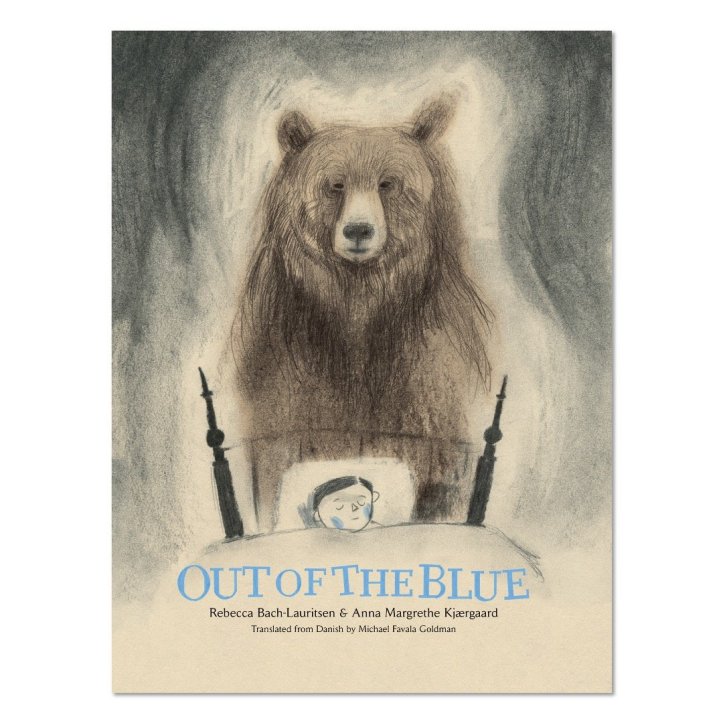

Out of the Blue

Written by Rebecca Bach-Lauritsen

Illustrated by Anna Margrethe Kjærgaard

Translated from Danish by Michael Favala Goldman

Published by Enchanted Lion, USA (2024)

Rhyme, alliteration, and spare text align with the highly structured life of the boy at the center of this story. He lives alone in a house where wall art and household items attest to his love of structure: botanical specimens labeled in Latin, “miles of books,” star charts, a telescope, metronome, piano, globe. Lined, checked, and herring bonepatterns on floors and walls reinforce the sense of order and invoke the blue-lined notebook and graph paper of schooldays. But despite a companionable cactus and days full of serene pursuits, the boy senses something is missing.

One day, disruptions manifest—shoes out of alignment, a broken pencil, footprints in the garden… After due research, the boy concludes that the culprit could only be a bear. But rather than fearing the creature or resenting the intrusion, he initiates a game of hide-and-seek. Bear joins in, and they seal the friendship over a fresh-baked cake. Tidiness no longer reigns supreme, but the boy has a friend with whom to play, make music, and share life.

Of these three titles, Kjærgaard’s pencil-sketched illustration style is the most finessed, and accords with the emphasis on precision and alignment. Blue highlights constitute the sole source of color, until the subtle red tones of Bear’s fur coat contribute a touch of warmth.

Lucky Me

Written by Lawrence Schimel

Illustrated by Juan Camillo Mayorga

Translated from Spanish by the author

Published by Orca, Canada (2023)

Everyone in Bruno’s life is lucky. His friend Sanjay has a pet iguana. When Bruno visits, the iguana becomes a dinosaur in a Mesozoic jungle where the two friends go exploring. Bruno’s brother Mateo has a dog, though it’s not exactly a pet. Mateo tells action-packed stories and can always remember where things are—sometimes for everyone in the family. When Bruno’s parents make the boys turn out the light at bedtime, Mateo can read in the dark with his fingers. But Bruno never tells on him. Bruno concludes that he is lucky, too, to have such a good friend and such a terrific brother.

Like Zahedi in Goodnight, Commander, Mayorga portrays a child’s world in strokes reminiscent of a child’s drawings. Animals, settings, and people—real and imagined—are rendered with varying degrees of precision. Select prominent details often suffice to capture the essence of a scene. Mayorga effectively conveys Bruno’s exuberant grasp on what is most important in life. His focus on what people can do and what they have—rather than what they can’t and what they lack—is sum and substance of this difference-embracing book. At a time when examples of conflict and self-promotion are so readily available, Lucky Me offers an endearing image of brotherly kindness and affection. A note and chart in the back introduce the Braille alphabet.

About Amanda

Amanda Bird is a freelance writer and editor living outside Eugene, Oregon, with her husband, teen daughter, and various international housemates. Her work in progress is a historical novel set in 1908 Tajikistan.

[…] Note: This post originally appeared on the World Kid Lit blog on Sept. 11, 2024 (Friendship Has No Formula – World Kid Lit). […]

LikeLike