by Anna Biazzi

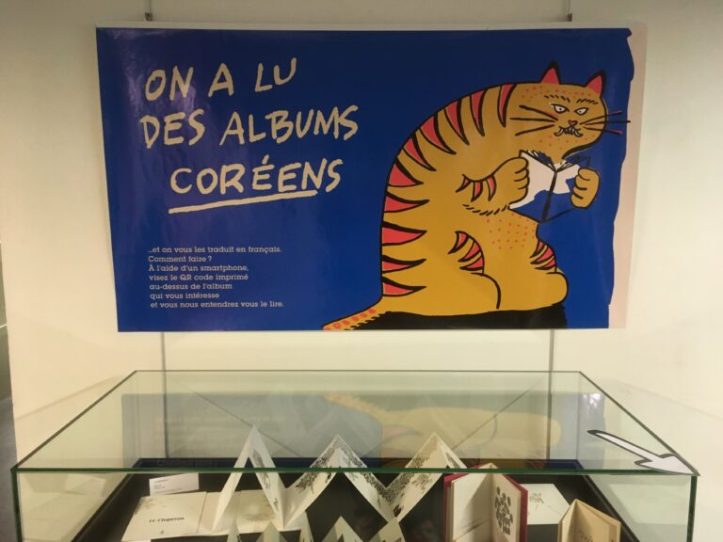

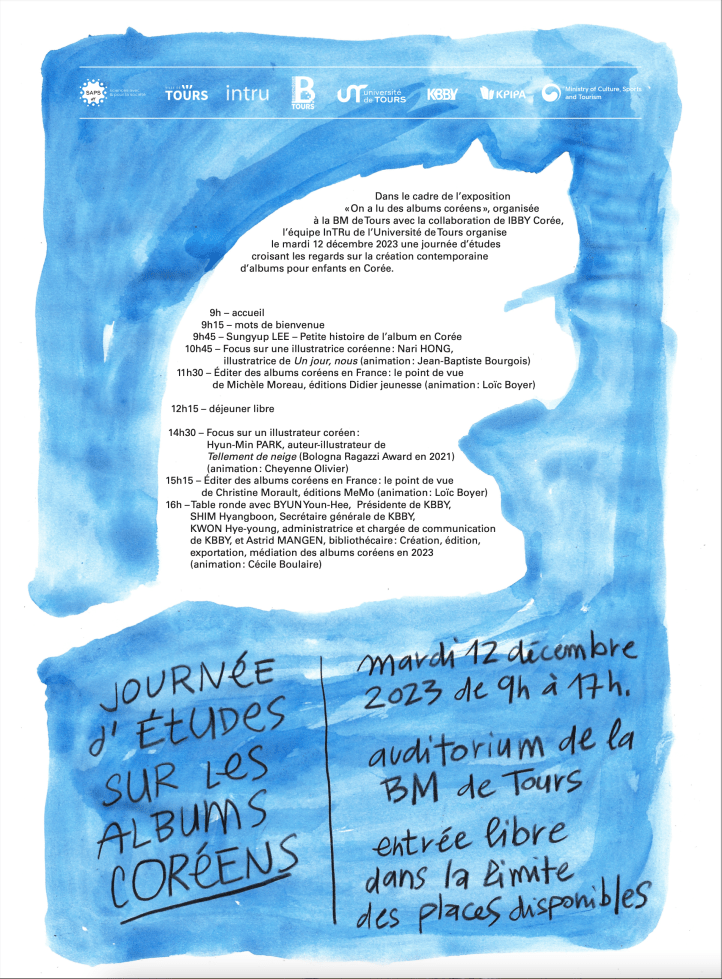

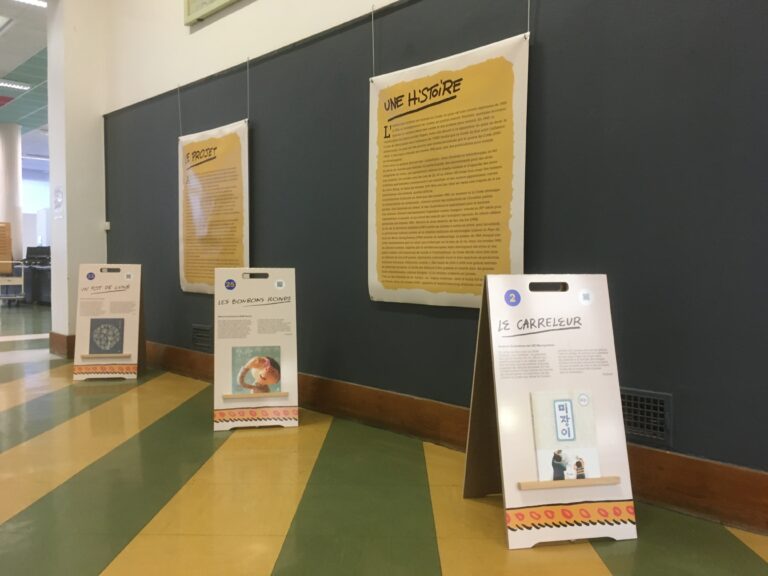

A group of French librarians, researchers and illustrators received a donation of contemporary Korean picture books by KBBY, which were not translated into French. They took the opportunity to approach the books as children would ̶-through the illustrations. They created a reading club and met throughout the year to exchange ideas and thoughts about the illustrations, stories and themes, with unexpected results that led to an extraordinary exhibition at the Municipal Tours Library.

Anna Biazzi from Chiara Tognetti Rights Agency brings our readers an exclusive interview with the organizers behind this unique translingual/cultural project: Cécile Boulaire, a professor of children’s lit, and Sungyup Lee, a researcher focused on picture books.

Anna Biazzi: Could you explain how the exhibition “On a lu des albums coréens” came about?

Cécile Boulaire: It all started with the arrival in Tours of Korean researcher Dr. Sungyup Lee, invited by the University of Tours. She arrived with a gift from KBBY, the organisation promoting Korean children’s literature: a parcel of forty recent Korean picture books, never before translated into French. We were amazed by these picture books, and immediately wanted to share this wonder with a wide audience. We decided that the books should be included in the public library collection, rather than at the university, so that they would reach a wider audience. We also decided to mount an exhibition designed for children. Our working assumption was that young children are open-minded, and since they can’t read, they won’t be worried about an unfamiliar written language. They’ll come with their parents, so we decided to write our texts for the parents.

AB: Who was involved with the project? Were they all from the publishing industry?

CB: The project members were mainly children’s librarians and researchers specialising in children’s books, graphics and illustration. Two of them were illustrators and one was a graphic designer.

AB: Which criteria were used to select the picture books? Were there any common themes that you recognised in the process?

CB: As we read and reread these books, we came across a number of recurring themes: the question of the human bond, particularly the bond between generations, but also the the bond with plants and animals (particularly in a stifling urban environment); the question of work, in a society that attaches overwhelming importance to it; the question of the environment, its preservation but also its destruction; and finally the link to history.

Sungyup Lee: The Korean picture books featured in the exhibition were divided into three categories, each chosen by its respective reading panel at KBBY (IBBY Korea). The first category was the Korean Nominations for BIB 2021 (Biennial of Illustration Bratislava); the second was Korean Nominations for Silent Books Lampedusa 2021; and the third category was books that received KBBY Special Mention designation in 2019 and 2020. As a result, the picture books in the exhibition were thematically and graphically diverse. Each book was chosen for its innovative graphics and themes, appealing not only to children but also sometimes to adults. The additional efforts by Cécile and her colleagues to identify thematic threads within these diverse selections was a thoughtful addition in organizing the exhibition.

AB: What was the aim of the reading club and the exhibition?

CB: We weren’t all the same age or the same profession and we didn’t share the same education or the same tastes. So we felt it was important that the exhibition reflected these differences, because they meant that we received these Korean picture books differently. We therefore chose to design the exhibition in such a way as to embrace everyone’s subjectivity: opinions on picture books are highly subjective. We decided that in order to write a panel presenting a picture book, you had to have a very strong opinion about it, a powerful subjective experience to convey to visitors. So we divided up the books according to the effect they had on each of us.

AB: This is not just an exhibition of picture books, but also the result of a long and deep exchange of points of view on reading illustrations and picture books. Could you explain how you showed this in the exhibition?

CB: At first, we didn’t have any translations, so we looked at the books without understanding the stories. Then Dr. Lee patiently translated the stories for us one by one. We were able to go back over each book with access to the content, and our outlook changed. Then we read and reread the books to compare them, classify them, and so on. Then some of us recorded the French translations aloud, so that visitors to the exhibition could listen to them (using QR codes). During this recording stage, the readers often ‘adapted’ Dr. Lee’s translations, because they were used to reading aloud to French children, and wanted the texts to ‘come across’ naturally. At the same time, we had regular meetings where we talked about the books, and our opinion of some of them changed. After seeing them repeatedly, some no longer seemed so exotic to us; others, which had seemed enigmatic to us until we had the translation, now seemed very classic; some, which had left us indifferent, moved us or amused us. The illustrators among us felt an affinity with the style and graphic choices of some of their Korean counterparts.

In short, as in any intercultural encounter, we began by finding the ‘Other’ very different from us, then less and less so, and in the end we realised just how much we had in common. To tell the truth, we didn’t pay much attention to it at first, but after a few months, we realized that we’d been placed in the very position of children. At first, we were looking at books without being able to read them, so we were exclusively attentive to the pictures, and we were trying to produce meaning with the pictures alone, their succession, their coherence. This sometimes led us to terrible misinterpretations! But we also became aware of the duality of text and image, and of the need to provide strong support for children: without language, the world remains incomprehensible to us.

We wanted to reflect this effect in the exhibition, highlighting the fact that children and adults are not in the same position when faced with a written object. But in the exhibition, it’s the child who is privileged! Indeed, we didn’t provide translations of the picturebooks, which the adult could have read aloud to the child, preserving his or her “authority” and cognitive superiority. Instead, we favored audio access, with a QR code allowing the child to listen to a voice telling the story from their parent’s phone. Of course, the adult can also listen, but in this case, the adult is also in the same position as the child–being read to.

AB: Do you think that the lack of cultural and historical information limited your reading experience?

CB: At the start of the project, we were in fact obsessed by this question. We worried our lack of knowledge of Korean culture and history was going to make us “miss” the reading experience. This is, of course, the case for some of the books, which bear witness to a specific episode in Korean history. But we also discovered that the picture book serves precisely to share cultural elements. After all, a small Korean child of five or six years old doesn’t know all the elements of Korean culture either, for example the symbolic importance of women fishing for pearls on Jeju Island. So, we discovered these cultural elements, their symbolic significance, and also what the authors were trying to make them say for the younger generation, just as a Korean child would have done.

AB: Did you uncover any of your own unconscious biases in the process?

CB: Unconscious biases are precisely those elements that difficult to become conscious of! It’s possible that, at the beginning or throughout the work, we gave too much importance to elements that, from our point of view, we judged to be “specifically Korean”: the question of the country’s partition into two political entities and the trauma this may have caused, or the perfunctory importance of work and social conformism in contemporary urban culture. But from our French point of view, it’s hard to recognize our own unconscious biases.

Of course, there are misunderstandings. For example, we were struck by the importance of the theme of work in these picture books, because it’s a subject that’s completely ignored in French picture books. But when we discussed our astonishment with our Korean guests from KBBY during the study day in December 2023, they didn’t seem to understand what we were talking about. They hadn’t recognized this theme as a common thread running through many of the picture books they had selected in advance.

AB: Through this project you had the opportunity to get to know more about the world of Korean picture books that our agency works on every day. What aspects, if any, did you find particularly interesting, different and/or enriching for a French reader about the way the picture book medium is realised in Korea?

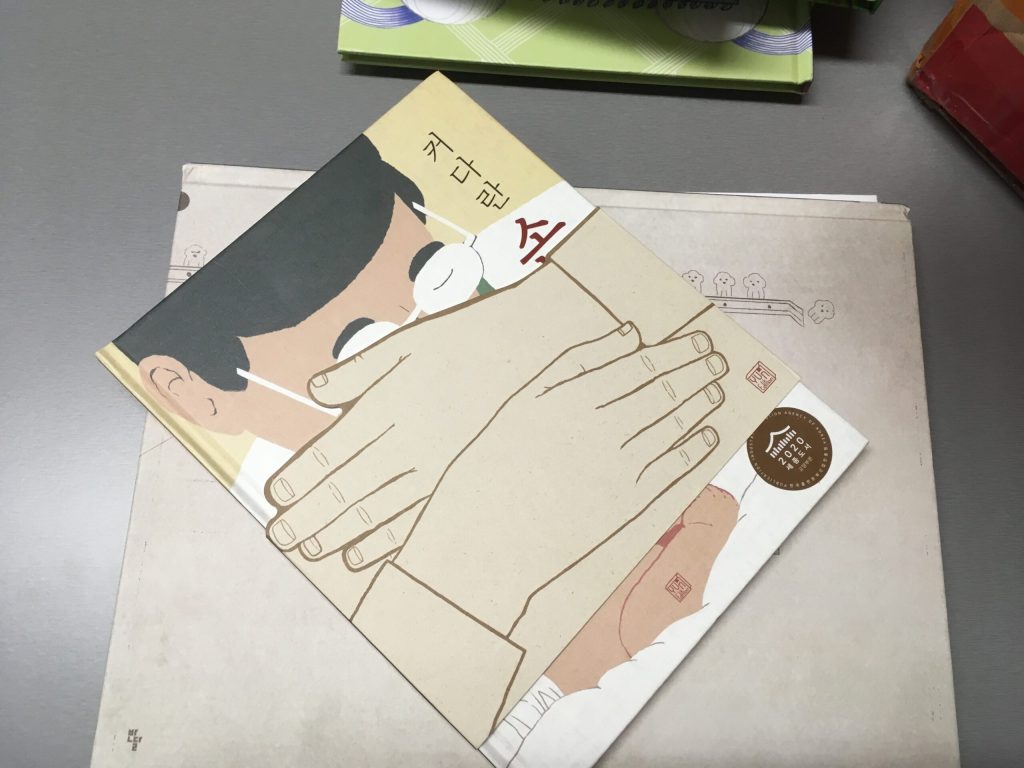

CB: What impressed us all was the production of the books: the work on the format, the material, the shaping, the exceptional quality of the paper and the printing. We had the impression of “haute couture”. The picture books that were selected for us represent the artistic pinnacle, but with a craftsmanship that the picture book industry in France rarely achieves. We also realized that these “exceptional” picture books are part of a deliberate ‘soft power’ strategy: the goal is to impress Western countries with dazzling cultural achievements that not only meet our expectations but also present an appealing image of Korea and the creativity of its artists. These picture books made us want to get to know the people who created them!

Cécile Boulaire is an Associate Professor at the University of Tours, specialising in children’s literature. She has been teaching in the French Literature department (bachelor’s and master’s degrees) and in the Faculty of Medicine (speech therapy school, and humanities courses for medical students) and has been Head of the Bachelor of Arts at the University of Tours from 2017 to 2021. She is a member of the InTRu lab of the University of Tours (Interactions, transferts, ruptures artistiques et culturelles). Her personal research on picture books is regularly published in the ‘research notebook’ Album ’50. She is a member of the Livre Passerelle association.

Sungyup Lee is the president of KBBY, the Korean branch of IBBY (International Board on Books for Young People). She is a lecturer and researcher at Ewha Woman’s University in Seoul, South Korea. Her research focuses on crossover picture books and translation. Since 2020, she has been focused on French crossover picture books published in the 1970s and 1980s with a five-year fellowship from the National Research Foundation of Korea. In addition to her research, she translates picture books between French and Korean.

Anna Biazzi is a children’s book foreign rights agent working with the Italy-based Chiara Tognetti Rights Agency. She is enthusiastic about connecting with foreign publishers, searching for new markets, keeping up with the latest publishing trends, and following the evolution of international intellectual property law.