By Ruth Donnelly

This week we talk to Claire Storey about her latest book, The Wild Ones, from Mexican author Antonio Ramos Revillas, a moving story of life on the streets of Monterrey, just released by HopeRoad.

Ruth Donnelly: First of all, congratulations on a fabulous translation. This is the third book from Latin America that you’ve translated for HopeRoad, as part of an Arts Council England-funded project you embarked on in 2021, and each of them is very different. Having previously given us a mystery based in 1900s Argentina and a pacey, twisty thriller from Uruguay (but set in Spain), The Wild Ones takes us somewhere completely new again, dealing with the realities of growing up in the heartlands of Mexico’s drugs cartels. Can you tell me a bit more about what drew you to these three books in particular?

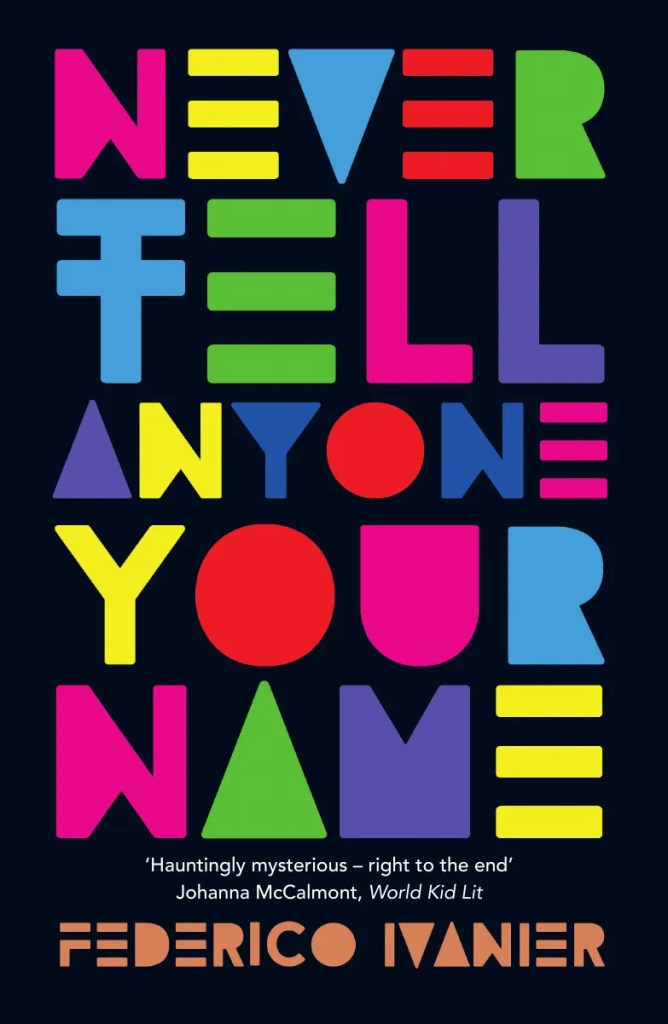

Claire Storey: In my application for the Arts Council England funding, I’d said I was going to look for one or two titles, probably in Spanish, and probably from Latin America, inspired by my work with WorldKidLit to look beyond Europe. And I ended up finding four, three of which I was lucky enough to get published, thanks to Rosemarie Hudson at HopeRoad. I was looking for books that would cross over well to the UK market, and I think The Wild Ones is the book that I expected might be most successful in that because it’s about topics publishers might expect from Mexico, but I also wanted books that would challenge publishers, good books that just happened to come from Latin America. The Darkness of Colours is a historical thriller and then Never Tell Anyone Your Name is very different again and that was part of the appeal. I was also looking for books that would challenge myself and showcase my talents as a translator, showing that I can do modern day, first-person narrative, or second-person narrative like in Never Tell Anyone Your Name. I can do historical thriller, and I can do the dialogue and slang that you find in The Wild Ones. The project also gave me the chance to test my own abilities – I might have found that actually I couldn’t do some of those things, and having the opportunity to find out what you can’t do is also quite useful.

RD: Moving on to The Wild Ones in particular, I was surprised by how moving the story was – the blurb doesn’t give much away and I was expecting a slightly romanticised, Breaking Bad-esque version of Mexican life, so reading about the gritty reality really hit home. As a mother yourself, did you find it hard to translate the scenes where kids as young as 12 were getting involved in gang warfare?

CS: Absolutely, and not just being a mother, but a mother of kids that age. My eldest is 14, and I’ve been working on this book since 2021/22, when he was 12, which is the exact same age as the middle brother in the book, Fredy. I don’t want to give too much away, but there’s a chapter towards the end of the book which is just four lines and it’s just heartbreaking. To have a son that same age, it really hits home.

RD: Why do you think it’s important for British kids to read about this subject matter?

CS: I think it’s important because although it’s very firmly set in Mexico, in many ways it’s a pretty universal story. There are some British kids who will be living very similar lives, and in conversations with Rosemarie Hudson, the editor, she said she had images in her mind of a place in the Caribbean. I’ve read a few interviews with the author, Antonio Ramos Revillas, where he says it’s not a story of exceptionalism, and I think that’s an important point. It’s not talking about someone who’s grown up in these difficult situations on the margins of society and then gone on to escape, make his millions and become an exceptional human being. That’s not to say that the protagonist, Efraín, isn’t an exceptional human being, but he is trying to live the life he wants to live within that community and that difficult situation. And maybe that is what a lot of kids can aspire to; they might not be able to escape their living situation, but they might be able to live in a different way in those same circumstances. It’s about where you draw the line between what is “right” and “good”, and what you need to do in order to survive. And Efraín is heroic to me, protecting his brothers and putting himself in the firing line at points.

RD: On that note, the main character, Efraín, has a real fight on his hands to prevent himself and his brothers from getting into trouble after their mother has been wrongfully imprisoned. Although they’ve grown up alongside drug dealers and gang members, they’ve always been taught the importance of getting an education and staying on the straight and narrow. How did you find the voice of this fifteen-year-old kid who is so torn between two worlds?

CS: I think voice was one of the biggest challenges in this book – the way young people speak, and making that feel authentic, without picking the whole story up and setting it somewhere else, which I really didn’t want to do. I did spend a lot of time listening to my kids talk, and watch videos on YouTube, which is a great way to hear young people speaking – with different accents and turns of phrase in English – but at the end of the day I’m a forty-something translator in the Midlands and I’m trying to produce the voice of a 15-year-old boy in Monterrey.

At the time I was translating The Wild Ones, my daughter’s primary school sent out a slang dictionary to all parents with lots of the terminology around drugs, gangs and violence. It was meant to make parents aware of warning signs – if you hear your child using these words, alarm bells should ring, but it came at a time when I was thinking about that sort of thing a lot, so it was interesting. It was also a reminder that children – even primary school age – can get caught up in this sort of thing, it isn’t isolated to Mexico. Of course, as one of my WKL colleagues pointed out, by the time these words have been collated by an organisation, made into a dictionary and circulated to parents, they’re already out of date, and the same goes with any text that involves slang – in ten years’ time it will probably feel dated and that’s just something you have to accept.

I ended up leaving some of the slang terms in Spanish, which as a translator can be hard because you feel like you haven’t tried hard enough to find a solution. But I had conversations with other translators – including some of the World Kid Lit crew – and I took some inspiration from some contemporary Latinx authors who are writing in English but throw in a lot of Spanish words. So that’s the route I decided to go down. I was quite specific that I didn’t want those Spanish words to be italicised. One example is the word ”compa”, which the characters use all the time. It’s short for “compadre”, which is like mate, but if I’d put “my mate Jeno”, it sounds very British. I could maybe have used “dude” or “homie”, but that didn’t feel right either.

RD: There’s also a lot of legal terminology in there, as Efraín is trying to navigate the Mexican legal system to get his mother released from jail. How much research did you have to do to translate that?

CS: I did have to do quite a bit of research. I’m fortunate that I have a friend who’s a barrister, and also some people I know here from Mexico who I was able to ask for help. It’s not just about me understanding the Mexican system, it’s about being able to convey that to readers in a way that they can understand..

And again, voice was a challenge because of course there are the lawyers and judges who are suddenly speaking very formally. Luckily I watch a lot of crime drama, which helped with that, but the narrative voice also changes. It becomes more serious, so I needed to capture that while recognising that Efraín himself was struggling at times to keep up with that change in voice.

RD: Was there any aspect of the original that needed to be adapted for British readers?

CS: Swearing. The editor was very clear that the swearing would need to be toned down for UK schools and libraries, because there are a lot of expletives in the Spanish text. So while there is the odd F-word in the translation, I have moderated it a lot. But it’s tricky to change swear words. As a parent, if I drop something on my foot in front of my kids I might say “flipping heck” or “oh sugar”, but this is a gang of fifteen and sixteen-year-old kids in really intense situations, they’re not going to say “fiddlesticks”, are they? So in some places I’ve had to completely step away from swearing and think, “what are they actually trying to express here?” At one point, one of them says “Seriously?” because what they’re expressing is disbelief, so that avoids swearing, but also avoids making it sound unnatural.

RD: Finally, I know that Federico Ivanier, who wrote Never Tell Anyone Your Name, has another book coming out in your translation next year. Do you have any plans afoot to translate more work by Antonio Ramos Revillas?

CS: That would be lovely, and I’m just working my way through reading a couple of his other books, La guarida de las lechuzas (The Owl’s Lair) and Playa Baghdad (Baghdad Beach) which is a novel for adults. I’ve actually started to refer to myself as a book scout as much as a translator, because I spend a lot of time pitching directly to publishers, and I think one of his titles might end up on my next annual list, which I usually have ready for London Book Fair.

This year has been super busy. As you say, I’ve got Federico’s middle grade book Sword of Fire coming out in May next year from Puffin Books, and also a translation from German, The Path, by Rüdiger Bertram, which is coming out in November from Dedalus Books. I also attended the Catalan workshop at this year’s Bristol Translates summer school, so I’ve got a few Catalan titles I’d love to find a UK publisher for, especially L’Assassina de Venècia (The Assassin of Venice) by Pol Castellanos, which I think is really great. Anyone who is interested can read more on the Spotlight on Catalan YA Fantasy page of my website.

Claire is a translator from German and Spanish into English. In 2021/22, Claire received funding from Arts Council England for a project focusing on YA Literature from Latin America. http://www.clairestoreylanguages.co.uk View all posts by Claire Storey

Ruth Donnelly is a Spanish-to-English literary translator, and mother/caregiver to three kids, two cats and a tortoise. Her main interest is in Latin American fiction, particularly children’s literature. A short story she translated will appear in Latin American Literature Today at the end of this year, and she spends most of her time, workwise, sourcing and translating new and exciting writing for children from Latin America. Samples of her work can be found on her website: www.ruthdonnellytranslates.co.uk