By Johanna McCalmont

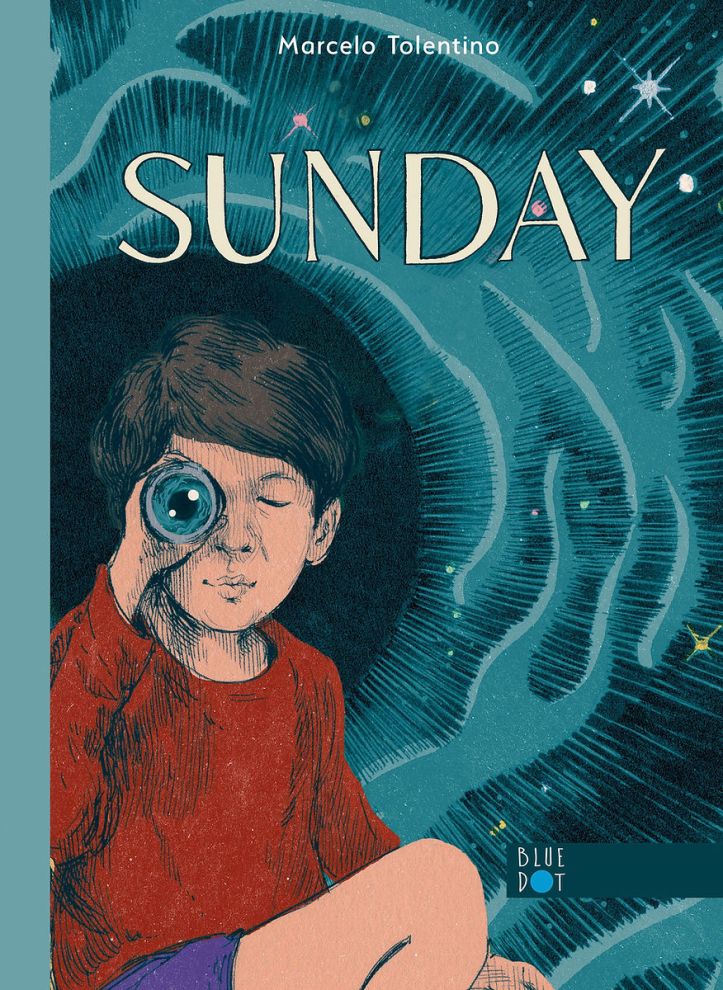

This week translator Rahul Bery tells us all about his translation of Sunday, an enchanting new picture book by Brazilian writer Marcelo Tolentino (Blue Dot Kids Press).

World Kid Lit: Sunday is a beautifully illustrated picture book with a magical feel. Can you tell us a bit more about the story?

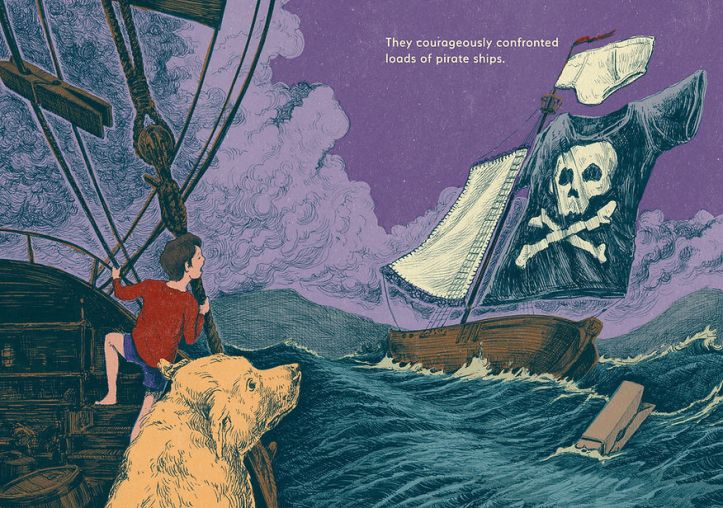

Rahul Bery: I’d say that, above all, it’s a lovely story about a family. It’s like a much nicer version of Not Now, Bernard by David McKee, where Bernard insists there is a monster threatening to eat him, and his parents pay no attention, not even when the monster does indeed eat him, and they just tuck it into bed without even noticing the change. In Sunday, there is a great sense of adventure throughout the book as the boy explores an imaginary world around his house one Sunday afternoon when everyone else seems to be busy doing other things. It becomes quite surreal at times too, with domestic objects like milk bottles and drying laundry becoming part of the epic landscapes through which he quests. This kind of reminded me of one of my favourite picture books from my own childhood that my own kids loved too: Maurice Sendak’s In the Night Kitchen.

WKL: I love how the story transitions from the everyday to the special, from tiny details around the boy’s house to the huge world still to be discovered. Do you have a favourite part?

RB: My favourite illustration is the one where the boy and his grandmother stare into each other’s eyes. There is something very mysterious about it. I have a gripe with a lot of kids’ books these days, often there is too much text and no sense of mystery. To have a huge pictures of eyes, infused with wordless emotion, is really unexpected and breathtaking.

WKL: What sort of reader do you think will enjoy Sunday?

RB: I think readers of all ages will enjoy Sunday. A lot of the picture books I came across at libraries when my kids were small really annoyed me: in many cases, the texts were very descriptive of the illustrations and not particularly exciting. Sunday is very different in that respect. It’s poetic and almost abstract in many places. It’s definitely one that adults will enjoy reading with children. And even now that my own children are in double digits, they still enjoy sitting down and having a picture book read to them. I can’t wait to show them the final copies of Sunday.

WKL: The text is quite minimal, yet clearly poetic. What was it like to translate?

RB: After my first draft, which was quite literal, I worked closely with the editor, Summer Laurie. She played an active role in ensuring the book as a whole worked for the publisher’s audience. One of the main things I needed to do was to make sure we kept a similar number of words in the English, but essentially Summer was the one who had to make a lot of the harder decisions. Some translators like to always have the final say on their translations, and I can see why, but for me, the editor/publisher is the one who actually has to sell the books. The buck stops with them. Especially with publishers like Blue Dot who specialise in translation, I tend to trust editors’ instincts and don’t often query cosmetic changes, within reason.

WKL: Were there any unexpected challenges or interesting solutions you came across while bringing the story into English?

RB: The hardest part was capturing the whole journey the character goes on. It needed to be as exciting as possible. At the same time, the text in English needed to be kept quite tight and I had to avoid anything that was too close to a ‘Latinate’ translation, so for example a ‘dense forest’ became a ‘fertile forest’. We also had the famously ‘untranslatable’ Portuguese word saudade, but, in this story, the sense of ‘homesickness’ was clear, so it wasn’t too much of a challenge, thankfully. In fact, to have saudade usually just means to be homesick, or to miss someone, or to fondly remember them, and it’s rarely used in the quasi-mystical sense that has made it famous.

WKL: You also translate fiction for adults. Did you find that you had to take a different approach when working on this picture book?

RB: Absolutely. The way the words look on the page is very important in children’s books. It really helps that I have read a lot of picture books over the last 15 years and that I have a hyper-critical eye towards them. I know how important the way the text looks and is arranged on the page is, from both the adult and the child’s perspective. There is a strong visual element to the text alongside the illustrations, and the number of words needs to stay similar. When translating from Portuguese and Spanish into English, I find that the word count generally increases, so I had to keep an eye on that. The text in Sunday is also very poetic, so we needed to keep that in the English which meant that we had to pay careful attention to the syntax and word order because they can change the emphasis. I would say that it felt like working on a prose poem.

WKL: You’ve also been involved in several programmes that promote languages and creative translation in schools in the UK, such as the British Library Translator in Residence, Translators in Schools, the Queen’s Translation Exchange (QTE) and the Stephen Spender Trust (SST) Poetry Prize. How do the programmes introduce children to languages? What sort of response have you had from the kids?

RB: Working with SST and QTE was a direct result of the residency at the BL, which I think I got partly because my application talked a lot about education and community engagement, which resulted in a day-long translation workshop with pupils from local primary schools in St Pancras and Somers Town. I’ve found that primary-age children, especially between the ages of around 7 and 10, will engage with almost anything as long as they enjoy it. They don’t have that cynicism around language learning that tends to set in with many British schoolchildren once they start secondary school. Since then I’ve done many workshops in different parts of the country, and the approach has always been simple – we introduce the book using images, introduce the text, translate it literally using glossaries and finally, after ceremonially tearing up the glossary, focus on making a fun, creative translation. The focus is not really on knowing the source language – in some cases it will be a language none of the participants have any experience of – but on the creative side of translation. Children are often the best judges of what works in practice! It’s also a great way to introduce children to authentic cultural materials in a given language, rather than the very dry stuff they are often exposed to. And picture books are ideal both because they convey meaning and context through visual and written language, and because so much of the meaning can be deduced without reading a single word.

WKL: And finally, have you got any other favourite stories from Brazil or Portugal?

RB: I recommend Mary John by Ana Pessoa (Arquipélago, 2022), a YA novel that I translated with Danny Hahn, a great coming of age novel with illustrations by Bernardo Carvalho. Ana is a brilliant writer, whose output includes novels, graphic novels and picture books, and she always works with brilliant illustrators. The Portuguese publishing house who put out her work – Planeta Tangerina – are absolutely brilliant, everything they publish is innovative and striking, and their production values are first rate. I’d love to translate some of Ana’s graphic novels, two of which – Aqui é um bom lugar (Here is a good place) and Desvio (Detour) – I have done samples for, as well as some of the Planeta Tangerina picture books, in case any publishers are reading this, check them out on the website!

Rahul Bery translates from Portuguese and Spanish to English, and is based in Cardiff, Wales. He is the translator of Kokoschka’s Doll by Afonso Cruz and Rolling Fields by David Trueba, which was nominated for the 2021 Translators’ Association First Translation Prize.