This week World Kid Lit regular contributor Katy Dycus interviews Catarina Sobral, a Portuguese illustrator and picture book writer, about her new book Ashimpa and her craft choices.

by Katy Dycus

Katy Dycus: The best picture books are created by great artists, and I so admire you as an artist. Your illustrations create a whimsical, witty narrative all their own. When I read your new book Ashimpa (Transit Children Editions 2025, translated from Portuguese by Juliana Barbassa), the first of your books to be published in the U.S., I was delighted to learn that the main character of your new book is actually a word – ashimpa – that no one knows how to use because no one knows its meaning or part of speech. What a funny love letter to language itself.

Catarina Sobral: Ashimpa was the second book I created during my Master’s course. My thesis was about how to transform what is verbal language into visual language. The first book, Strike (Greve in Portuguese), is also a play with language. It’s about points going on strike. In Portuguese, the words “dot” and “point” are the same.

Katy: So, no one is dotting their “i’s,” exclamation marks, question marks, or semicolons, and the colon disappears completely.

Catarina: And with points on strike, other things disappear – the vanishing point, the meeting point and points of view. The point has so many meanings, and I decided to explore that. With Ashimpa, I was interested in exploring parts of speech.

Katy: Did any complications arise in translating Ashimpa from the original Portuguese, since the mechanics of language, grammar, and the way we use parts of speech vary from language to language?

Catarina: Not that I know of. From the languages I speak or understand – Spanish, English, French, Italian – there were no changes in meaning from the original. The book is in a different alphabet only in Chinese.

Katy: How many languages has the book been translated into besides the ones you mentioned?

Catarina: It’s also in German, Turkish, Polish, Hungarian and Swedish. 10 languages in total. Although in English, we have the Transit version but also slightly different versions in other places – in the Philippines, in Singapore and Malaysia.

What’s most interesting about Ashimpa is the word doesn’t exist, but it was still translated! Like in Swedish, it’s Atjimpa, and in Hungarian it’s Asimpa. In Italian it’s Cimpa, because the sh sound becomes a c at the beginning of a word.

Katy: How fascinating! Words take center stage in Ashimpa, but I’m just as curious about the visual language of the book. There’s a deceptive simplicity of line and color and yet a kind of depth. How did you achieve that?

Catarina: I used a lot of wax pencils in this book. I layered them directly on paper, usually colored paper. So, it’s not very well rendered, the technique is a bit childish, or tentative. I didn’t create a perfect green, for example. I used two greens to create one on the paper. That replicates the spirit of the text. The text is funny, and I wanted characters that looked a little funny, too. Different types of legs, for example, some stretched out.

Katy: And how did you know when you had finally arrived at the final stage of illustration, like when you say to yourself, “This is working, I’m happy with this. I think I’m done.”

Catarina: That’s a really good question, and I don’t know quite how to answer it. There are a lot of things I’ve been learning since I’ve been teaching illustration. How to express to students why a composition is balanced, why a color contrast is working or not. Because of that, I now have shortcuts in terms of composition or color palettes. But that raw sense of “it stays” is very much intuitive.

Katy: How does teaching illustration complement your practice?

Catarina: It’s a way of having to put into words and make sense of the choices I make during the process of illustration without thinking too much about why I’m making those choices. When I have to explain, I somehow see the process in parts, and I can understand the reasons behind it. But it also helps because I’ve been teaching mostly narrative in illustration, so it helps in understanding how narratives in picture books work. The narrative arc, how can we draw that? I also get inspiration from students as well, and that feeds my work.

Katy: Have you noticed any recurring themes in your books?

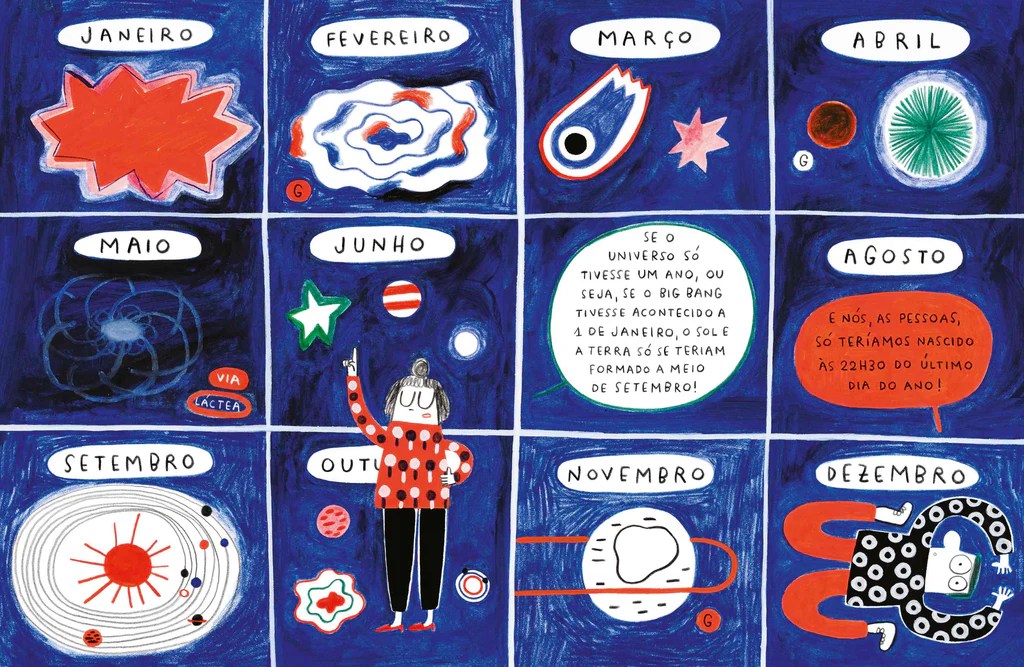

Catarina: I’ve done some books about living with others, sharing our home, sharing the planet, not just with people but with plants and animals. The themes of sustainability, tolerance and empathy come up. For instance, I have a nonfiction book about the story of the universe, and I explain everything about astrophysics to reach the point of why we’re all made of stardust.

Katy: I think I can see this theme in Ashimpa in a way: trying to understand something – in this case, a new word – together to come to a collective understanding.

Catarina: That’s an interesting observation. A Brazilian journalist who commented on Ashimpa said that “language is something that belongs to the speakers.” It made me think about how we use inclusive language, how we change language to reflect our values and what’s happening around us. It changes because we are in context, and that sentiment also has to do with living with others.

Katy: We make language what we want it to be as we’re speaking it, and like you said, the more inclusive our words, the more others feel like they belong, that we all belong.

In what other ways do you feel your work resonates with readers?

Catarina: I usually say my work has three vectors. One is permeability; it has to do with being simple. Being reduced to the essentials – not being too descriptive. The way children talk, they reduce their communication to the essentials. They remove what’s accessory. I compare children’s books with poetry or haikus or flash fiction. You have to say the essential.

Katy: An economy of words?

Catarina: Yes, and in the relationship of words to pictures, to leave enough space for the reader to fill in the blanks. The Brazilian journalist’s comments about Ashimpa shows perhaps what she struggles with or thinks is important, and another person would read it differently. There’s enough openness in the book so that it can transform into the reader’s own story.

Another thing is I try not to infantilize the audience. I create layers of meaning so that it can be interesting for adults to read as well. The picture book should open doors and be a mirror to the reader. If children encounter a style they’re not used to, maybe it will be interesting for them to know something more about it, so the book can be the beginning of something.

And everything should start from the emotions, that’s the best way to communicate with children and probably with everyone.

Katy: Which emotion is most important for your work?

Catarina: Honesty. When you get to the point where you can say, “Ok, this picture is how it should be,” or “this text is how it should be,” when you find that thing you cannot name – which has to do with intuition—I think it relates to being honest with yourself. What you want to express. If the emotion is yours, it will transcend the page and reach the audience.

About Katy Dycus

Katy Dycus writes for the Department of Anthropology at Texas A&M University. Her essays and reviews appear in Appalachia, Necessary Fiction, Harvard Review and The Wild Detectives, among others.

Support World Kid Lit!

World Kid Lit is a nonprofit company that aims to bring diverse, inclusive, global literature into the hands and onto the bookshelves of young people. We rely on grants and donations to support our work. If you can, please support us at Ko-fi. Thanks!