by Katy Dycus

I met author/illustrator Manuel Marsol at Feria del Libro de Madrid in June 2023. I was 7 months pregnant with my son, and Manuel had his own baby boy in tow. He signed a couple books for us: Yōkai (Fulgencio Pimentel 2017) – which received the International Illustration Prize at Bologna Children’s Book Fair – and O Tempo do Gigante (Orfeu Negro 2017). Manuel’s otherworldly illustrative style is perhaps best exemplified in his new picture book out this year, Astro (Transit Children’s Editions 2025), translated into English by Lizzie Davis.

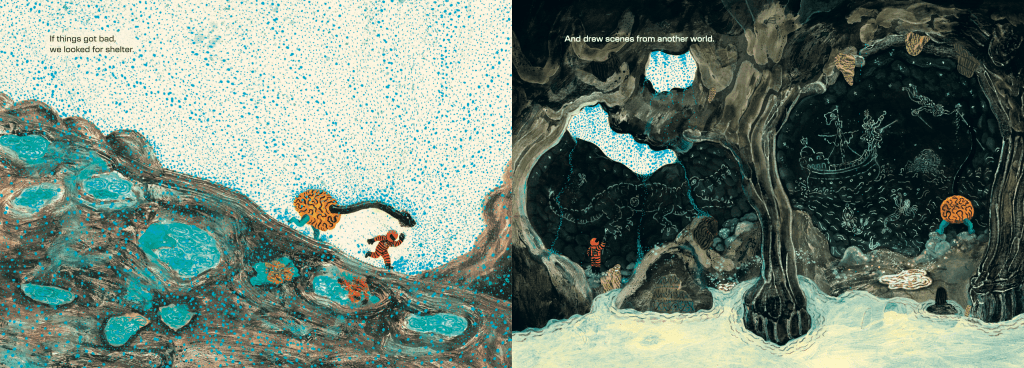

Katy Dycus: One theme I see across your books is the transformative power of landscape. In your latest picture book Astro (Transit Children’s Editions 2025), a tiny astronaut befriends a creature on a faraway planet and together they navigate its strange terrains.

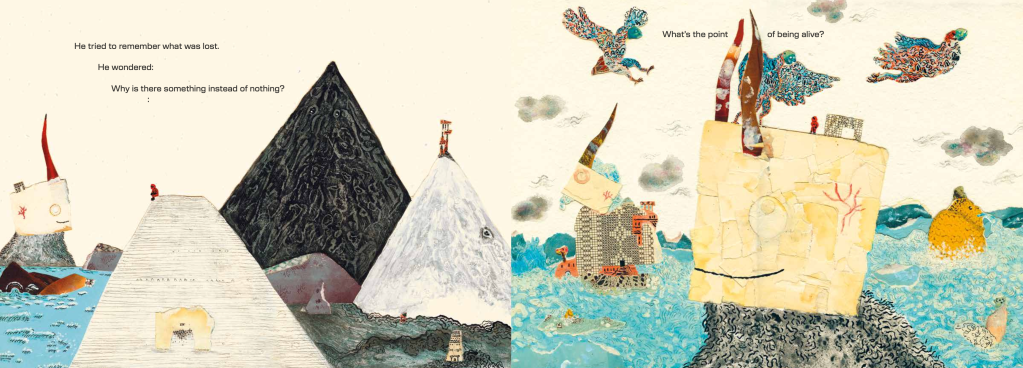

Manuel Marsol: I’ve always been inspired by German Romanticism, especially painters like Caspar David Friedrich. These artists wanted to say: we are nothing in the universe, yet we have the power to imagine. The real trip isn’t to the horizon or into nature but to yourself. I use these landscapes, these places that transform me, because I want to dive into the meaning of myself and the meaning of life. It’s a trip to the interior.

Katy: Astro is the externalization of an interior seeking, in other words. And it deals with loss. I know this book is deeply personal for you. Can you share?

Manuel: My father died of cancer when I was eleven years old. I always say, even if I lost him early, eleven years in a child’s life is a huge thing, and I have a lot of memories. He was a history of art teacher, and he used to paint with my sister and me.

In the beginning, when I started Astro, I didn’t say I was going to do a book about my father – not at all. If I’d had that idea in mind, it wouldn’t have worked. I believe that with art, if you have a plan, it’s not fresh.

With Astro, I was just exploring. My father’s best friend is an abstract painter – Paco López-Soldado – and I grew up surrounded by his paintings which are full of these textures that appear in Astro. For me, those paintings are a kind of universe.

When I quit my career in advertising, I spent three months painting with Paco. It was a way to know my father in some way, too. It was really healing. In those months, I learned some of his techniques. They involve, in some cases, a mix of oil with acrylics, which are different mediums that normally don’t mix well, but they generate stains and accidents.

Katy: It sounds like the technique is about elevating imperfections.

Manuel: Yes, and I started to think that these stains and accidents could be a landscape. Paco is an abstract artist, but I wanted to be figurative as an illustrator. I thought, how can I make this into a figurative world?

I’m not this kind of illustrator or painter who’s really skillful with drawing things perfectly, creating realistic detail. So, I took my instincts and mixed them with my lack of skills, you could say. I think these effects make my style. I was so happy to just let the landscape appear in front of me, as if by chance.

Suddenly a strange planet appeared. It’s a planet of the imagination but also from my memory. Then onto this landscape I introduced a tiny astronaut because I thought it could be a nice character, but soon I realized this character wasn’t behaving like an astronaut but more like a child.

Katy: I like that this character had an agency of his own, apart from you.

Manuel: He inhabits this landscape that is one of memory, it’s full of gaps since our memories aren’t intact. This memory is full of hidden places and full of monsters and dreams. And this book also speaks about time. If you think about it, time is flowing through all the pages of my books. Time is very related to my biography with my father, as well. I’m always trying to control time in some way.

Katy: Trying to recover that time you had with your father, but also recovering lost time and holding time still by making these memories permanent through art.

Manuel: When I draw, it’s like a time travel machine. This time on that planet is like time spent with my father in some way.

Katy: It’s a journey you take to the past.

Manuel: Into the past and into myself.

Katy: But paradoxically, the book is about space travel, which feels so futuristic.

Manuel: I love science fiction, which is kind of transcendental; it asks big questions about life and death. In Astro, I wanted to emphasize this “outside of time” place. Some lines from the book read: “I no longer remember when Astro came to visit. It was a long time ago. Maybe thousands of years.”

You don’t know if you’re in the past or in the future. I wanted to create that feeling because memory is something like that. You don’t really know where it’s placed. It almost exists outside of time. Even with the alien who dies, he keeps talking and you don’t know from where or from when.

Katy: Just like the landscape you create, this sensation of voice is fluid. The line between the real and the imagined isn’t secure.

Manuel: When you’re a kid, you don’t know where that line is. You go from one to the other in the same second.

Katy: I guess that’s the purpose of children’s literature. To treat that line as permeable.

Manuel: And when you read this book as an adult, you recover that emotion in some way. My main objective with books is to be in front of the mystery. And time is a big mystery to me. So is the unknown – space, the sea, the forest.

Katy: We are fascinated by mystery throughout the life course so, as you said, we can recover these emotions as adults reading picture books. Not only do you write for kids but for adults, for all ages.

Manuel: I want to think that my books are for everybody, from age zero to one hundred. I think of the books and movies that inspired me as a kid. I like them for different reasons when I read or see them now as an adult.

I understand there are some metaphysical or existentialist themes in my books – far from the knowledge of kids – but I also remember myself when I was a kid. It’s very common for children to ask big questions. It’s all about mystery. When kids and parents go into the forest, what’s on the other side? We all ask these questions.

Katy: In Astro we find themes of loss, fear, confusion – things that parents like to shield their children from.

Manuel: Parents are afraid of stories that can scare children, but I like to say that if children are a bit scared, they go to find their parents’ love. I remember that feeling. I used to hug my parents when I was scared, and that is a good thing. Fear also makes us ask more questions. Fear, as you know, is part of life.

Katy: Because your book is so different from anything that exists in the world of children’s books, did you have difficulty publishing it?

Manuel: Astro is ten years in the making. I startedin 2013 and Orfeu Negro first wanted to publish it, but it was still a work in progress at the time. They later rejected it because it was very expensive to produce. Then, a Spanish publisher was interested but thought it was a bit risky. The style is very arty, not the kind of thing you see in bookstores, even less so for kids.

I was also stuck; I didn’t know how to make it work so I abandoned the project in 2016. I thought it was just part of my process, because from Astro came a lot of other books like Yōkai. But in 2019, the editor in chief of my Spanish publisher Fulgencio Pimental was really in love with the possibilities of this book and encouraged me to continue, but we soon dropped it again due to creative differences. Finally in 2023, during the course of one week, we moved some pieces around and it worked. I always say it’s a miracle that this book exists.

Katy: I’m glad it exists. It fills a gap in children’s literature.

Manuel: It seems to me that most picture books nowadays are books that want to serve a function. These books want to change fiction into something practical. But I think the purpose of children’s books is literature, emotion, and art. In the case of Maurice Sendak, it’s poetry, entertainment, drawings, and above all, the music. Of course, we see the power of the imagination to solve problems, but he doesn’t make this message explicit.

Books need the element of surprise. The idea for a story has to be something that you follow in the night. It appears and if you’re in your pajamas, you have to get out of bed and follow it. I draw because I want to know what the drawing brings to me. I can have a small idea like wanting to speak about the mysteries of the forest but nothing else. Then I start drawing and the story appears.

To learn more about Manuel Marsol, visit his website: manuelmarsol.com / @manuelmarsol

About Katy Dycus:

Katy Dycus writes for the Department of Anthropology at Texas A&M University. Her essays and reviews appear in Appalachia, Necessary Fiction, Harvard Review and The Wild Detectives, among others.