By Katy Dycus

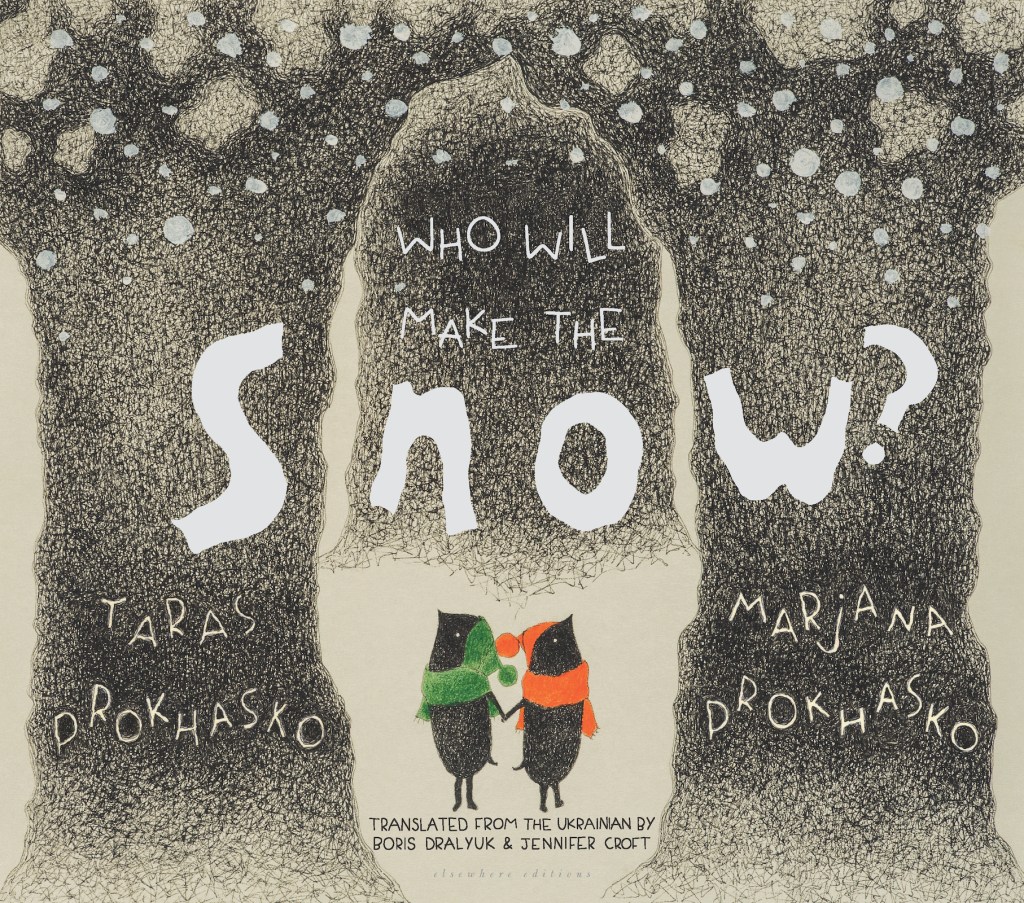

Boris Dralyuk is a poet, critic and translator (translating from Ukrainian and Russian). Who Will Make the Snow? is the first children’s book he has translated, alongside writer and translator Jennifer Croft. In this conversation, we discuss the music of language, softening difficult messages for children, and what makes Who Will Make the Snow? distinctly Ukrainian.

Katy Dycus: You are a celebrated translator of several authors of adult fiction: Isaac Babel, Andrey Kurkov, Maxim Osipov, Mikhail Zoshchenko, among others, and in 2022 you received the inaugural Gregg Barrios Book in Translation Prize from the National Book Critics Circle for your translation of Andrey Kurkov’s Grey Bees.

How did you come to translate the Ukrainian children’s book Who Will Make the Snow?

Boris Dralyuk: I’m always looking for new challenges as a translator and I’m a great fan of writing for children in Slavic languages, especially of poetry aimed at children or poetry that takes into account the voice of children. This book came to us as an offer from the publisher. And as soon as we received it, both Jenny [Jennifer Croft] and I immediately knew we had to do it, especially as we had our own kids on the way and very much wanted to translate something they would enjoy when they were old enough to read it. So, in a way, the book grew up right alongside my infant twins. Having them on my lap, as I translated, was an intensely satisfying experience.

KD That’s incredibly special since the book is about a pair of mole twins, Purl and Crawly. Since this is the first children’s book you’ve translated, I’m curious how you select your projects.

BD: With time, as you gain experience, in any art form but translation in this case, you develop an intuitive sense of what will and will not work in your hands. That doesn’t mean that you end up tackling the same sort of thing over and over again. Quite the contrary. You get an intuitive sense of whether something you’ve never tried before will come out based on the vast range of things you’ve translated before. You become familiar with your repertoire of possibilities, with the number of tones you can master in English, the number of voices you have at your disposal as you’re translating. When something comes along in any of the languages you speak, you recognize in the tone and the voice of the original a possible tone and voice that the book will take on in English, and that’s what happened here. I heard something: a light note of irony, a gentle melancholy that I’ve encountered before, that I’ve been able to produce before. I knew that, between the two of us, Jenny and I could do this quite well.

KD: I like that you’re speaking in musical terms. You’re describing it in a similar way to how a musician might choose a musical piece to perform.

BD: I think you’re right, you’ve picked up on something crucial to our work: the music of language is almost as important, if not equally as important, as the sense. They go hand in hand. Each word has its range of meanings but also its musical sound, its aura.

KD: Could we think of different translations of a text as musical variations on a theme?

BD: Yes! I will admit something that should be embarrassing: I still sound things out in my head as I read. I have a very clear sense of what something ought to sound like when I read it. I’m not just scraping the surface for meaning, I’m drinking the whole thing – sound, sense, and all.

KD: With Who Will Make the Snow? you and Jenny collaborated as co-translators. How did that work?

BD: I did a draft of each chapter, she went over that and made the changes she wanted to make, and then I used the changes she made to that first chapter to guide my sense of what the second chapter ought to sound like. Then she’d make corrections to that. We went back and forth, chapter by chapter. I’d do a draft, perhaps not as carefully as I normally would if I were translating by myself, knowing she was there on the other end to refine it and add her own music. We don’t collaborate frequently, but it was such fun, such a pleasure to do, that I think we’ll look for more opportunities.

KD: Another coincidence is that Who Will Make the Snow? was written by real-life partners, like you and Jenny. Did you get to interact with Taras and Marjana Drokhasko?

BD: No, we didn’t. We translated this book at such a demanding period – the first six months of our twins’ lives. We didn’t have time for anything but the work and feeding and changing. So, we didn’t communicate with them, but I know that the text went to Taras and Marjana through the publisher and got their approval. It was only after the work was finished that we sent it off. That isn’t unusual for me, or for Jenny either. We tend to finish the translations we’re doing and then share them with our authors.

The goal for a translator, at least for me – I don’t want to speak for the entire community – isn’t to render any individual word, or to render any individual sentence. It is to render a whole. We want to create a text that stands on its own in the target language. I feel that it’s very hard to judge the whole text by just a rough draft of one chapter, or part of the whole.

KD: In other words, a translated text is its own separate entity that comes from the original.

BD: A bit like the interpretation of a jazz standard.

KD: I reread the book last night right before bed, and you know what? I really believe I slept better because it left me with the warmest feeling. I imagined myself in the moles’ burrow, their tiny tea cups hanging by the “branches” of underground roots.

BD: The book was written before the launch of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. It’s really a book about helping children sleep at night when facing an uncertain existence, an existence that has death at its margins. Whether war is raging around us or not, we all have to confront the fact that our time here is limited, that the people we love won’t always be here. The book’s great contribution is to soften that message, to make that message easier to receive and to show children that they are not alone in their existential dread and confusion. It also, I hope, gives parents a sense of how to handle difficult questions.

KD: And there is nothing softer than snow. In the book, Crawly asks Mama what happens to moles when they die, and she tells him, “The heavenly moles make the snow, and when winter comes, they send all the snow down to the ground.” Later, an owlet informs Crawly that it’s not just moles but all creatures that make the snow, since everybody dies.

As a Ukrainian book, its first intended audience is Ukrainian children, and in Ukraine, I imagine, snow is a common experience. So, putting these concepts into terms that children live and experience is a nice choice. What else is distinctly Ukrainian about this book?

BD: When I translate, my first goal is to communicate the unique qualities of a text, to reproduce the effect of the original on its readers. Yet I also want to show readers in English that Ukrainians (in this case) have as broad a range of emotions, as deep and as surprising an imagination as they do.

What I see as distinctly Ukrainian in this book is the gentle humor, the sly wink. The quirkiness and charm of the characters are very Ukrainian to me. And the way adults treat the children with enormous respect – almost as peers. Taking good care of them, of course, but also not talking down to them. That’s something very familiar to me as a Ukrainian-born person.

KD: Can you tell me about your journey from Ukraine to the United States?

BD: I was born in Odesa and moved to the States when I was eight years old. It was exciting and traumatic, to be pulled from one cultural milieu and dropped into another. I wanted to fit in as quickly as possible, so I threw myself into English, to the detriment of my native languages of Russian and Ukrainian. Later, when I was about thirteen years old, I began to recover those languages, having realized they were more of an asset than a liability.

I asked my mother for advice on how I could brush up on Russian and Ukrainian, and she said I should start reading poetry. In both Russian and Ukrainian, as in English, stress is dynamic. You never know where the stress falls in a word, and you’ll never know how it’s pronounced until you hear it pronounced. And most of Russophone and Ukrainophone poetry, up until the early 21st century, was written in meter. The meter determines where the stress falls in a line of verse. When you see a word in a certain place in a line of verse, you know where the accent falls. Reading poetry helps you learn not only the sense of words, but also their pronunciation, their music.

What poetry also teaches us – especially if you’re translating poetry that is metrical (or formal) into some version of Anglophone verse – is that you can’t keep things exactly the same. You can’t maintain the order of the words or even the order of the lines if you want to convey both the sense and music of the original. I take that lesson from poetry and apply it to prose. A sentence may not be a poem, but it is a musical composition. It does have a rhythm of its own, and in order to create a sentence as rhythmically engaging, as dynamic, as interesting as the original, one has to massage things, switch things around, work with the orchestration of it as much as with the sense of it.

KD: Children’s literature is often read aloud, and in reading aloud we are brought together. In Who Will Make the Snow? the Under the Oak Café serves as an important place in which to gather, a place where the animals go to cool off in summer, warm up in winter, and hear the gossip of the forest. And literature offers another kind of gathering place.

BD: It’s like being on an enormous conference call. You are reading in English to your children the same story some family in Ukraine is reading to its children in Ukrainian. You are, in that way, together.

KD: We are united with our fellow Ukrainian readers. Since the war began in Ukraine, do you think books like this are being received differently? Is reading more urgent than ever?

BD: I think so. The aim of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is genocidal in the sense that the Russian state intends to destroy Ukrainian culture, to undermine the validity of the Ukrainian language. Ukrainian people have been adamant about preserving their culture in wartime, maintaining their publication schedules, getting their literature out into the world, holding book festivals. President Zelensky himself attends book fairs and will go booth to booth to review the latest publications.

Among the components of the civilian infrastructure that’s been attacked by bombs, missiles, and drones are publishing houses (including one of the biggest publishing houses in Ukraine). This constitutes a direct assault on the language and the literature, and it only hardens Ukrainians in their determination to keep going, keep writing, keep reading, keep telling their stories. Many authors have taken up arms and have been killed, and many journalists have been killed in targeted attacks. Their determination is all the more admirable and impressive because they know their lives are on the line.

Who Will Make the Snow? and books like it have taken on new meaning because what is otherwise an omnipresent but vague threat – the threat of death, of the loss of loved ones – has become an imminent, highly visible threat for most Ukrainian children. It isn’t an abstract fear. It’s daily reality.

***

Boris Dralyuk is the author of My Hollywood and Other Poems (2022), editor of 1917: Stories and Poems from the Russian Revolution (2016), co-editor of The Penguin Book of Russian Poetry (2015), and the translator of Isaac Babel, Andrey Kurkov, and other authors. His poems, translations, and criticism have appeared in the New York Review of Books, the Times Literary Supplement, The New Yorker, The New Republic, Best American Poetry 2023, and elsewhere, and he is the recipient, most recently, of the 2022 Gregg Barrios Translation Prize from the National Book Critics Circle and of a 2024 Literature Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Formerly editor-in-chief of the Los Angeles Review of Books, he is currently an Associate Professor of English and Creative Writing at the University of Tulsa, a Tulsa Artist Fellow, and the editor in chief of Nimrod International Journal.

Katy Dycus works for an academic department of anthropology. Her essays and reviews appear in Necessary Fiction, Appalachia, and Harvard Review, among others.

World Kid Lit is a nonprofit that aims to bring diverse, inclusive, global literature into the hands and onto the bookshelves of young people. We rely on grants and donations to support our work. If you can, please support us at Ko-fi. Thanks!

We earn a small commission every time you buy books via the affiliate links on our site, or via our booklists at UK Bookshop.org. This is a much appreciated donation towards our work. Thank you!