By Katy Dycus

Tal Goldfajn is a translator and linguist in the Spanish and Portuguese Program in the Department of Languages, Literatures, and Cultures at UMass Amherst. Her recent English translation of the beloved Brazilian classic Marcelo, Martello, Marshmallow by Ruth Rocha (Tapioca Stories), was selected by the United States Board on Books for Young People as a 2025 Outstanding International Book.

In this conversation, Tal emphasizes the importance of translation in preserving cultural narratives and expanding access to diverse stories. We discuss the role of translation in children’s literature, the impact of cultural norms on translation, and the significance of bilingual storytelling as a form of engagement. Tal also highlights her collaborative work with students at the Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art, where they perform translated stories, fostering intergenerational dialogue and strengthening connections between multilingual storytelling and communities.

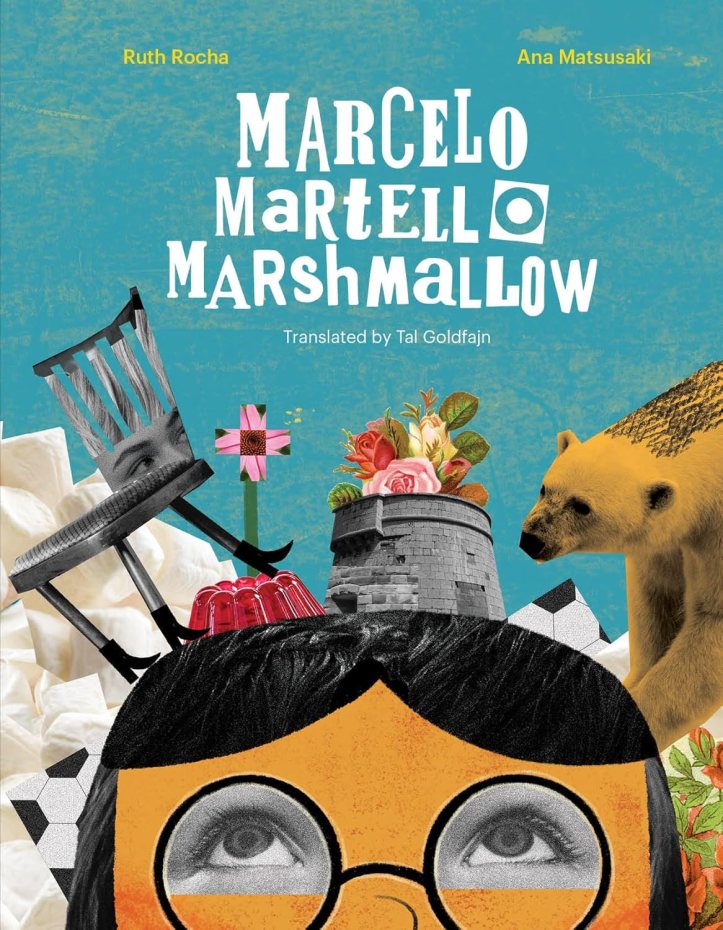

Marcelo, Martello, Marshmallow

Written and illustrated by Ruth Rocha

Translated from Portuguese by Tal Goldfajn

Published by Tapioca Stories, 2025

Buy from Tapioca Stories

Katy Dycus: Marcelo, Martello, Marshmallow is a love letter to language itself. Would you say language is the main character?

Tal Goldfajn: It is! I’m a linguist, so the books that I like to translate have to do with language. Marcelo is very special, he’s asking the simplest and deepest questions about language.

KD: Like “why is a table called a table?”

TG: I’m attracted to books that are considered the so-called “untranslatable” ones. There’s a French philosopher and translation theorist Barbara Cassin, who wrote the Dictionary of Untranslatables. We see this idea that untranslatability isn’t that we cannot translate a text but that we cannot stop translating it. In other words, it’s infinitely translatable.

I think the reason Marcelo was considered, in a way, untranslatable was because of all the wordplay, or nonsense words. If you think that translation should be literal, then your range of movement is constrained. As translators, we always recreate, it’s a question of what kind of recreation is requested.

KD: How did you get to the words blastflame or dogstayer or good sunning? When I was reading I thought, how did Tal translate this?

TG: I’m very glad you’re asking. Marcelo is a little boy who’s very curious and very unhappy about the relation between words and things, which is a profound philosophical question. That’s something I love about translating children’s literature. Children’s books often have a shadow; deep questions are lurking there. In Marcelo’s case, it’s the question of language, the way we relate to the world, how we construct a way of being in the world and interact with others through language. And here is Marcelo asking very innocently about why a table is called a table.

Marcelo is resisting a very basic thing, which is the arbitrariness of language, the idea that there is no natural or necessary relation between a word and what it refers to. He wants words to be motivated, to feel that they have some “natural correctness,” that there is an intrinsic connection between sound and sense, and in doing so Marcelo taps into a long-standing discussion about language that goes back to antiquity. The crucial thing was to see how Ruth Rocha built that language and to ask: what were her building blocks? What she does is really more lexical and morphological: she plays with word formation, dismantles clichés and invents unexpected rhymes. And the humorous element is directed at both adults and children.

Translation doesn’t merely transfer meaning from one language to another, it’s not a transfer shuttle from point A to point B. Translation opens a new field of associations, memories, and cultural resonances. Translation is often transcreation, a term used by the Brazilian poet and translator Haroldo de Campos. The language Marcelo ends up inventing in the original to better fit his world is based on the Latin roots of Portuguese.

In the English translation, I could not build it solely from the Latin layer of the English language. I had to use the Germanic layer as well. I play with sound structures and morphological twists that are not necessarily present in the original Portuguese. But ultimately I applied the same strategy Ruth Rocha had applied in her invented language: I tried to find morphologically possible but non-existent words in English as she had done in Portuguese. I was also guided by the musicality and rhythm of the words and sentences. For me, playing games with translation involves both exploring the malleability and creativity that languages allow as well as listening to each language’s unique linguistic memory.

Maybe you remember Marcelo’s mother saying, “a rose is a rose is a rose.” Well, that’s Gertrude Stein, the icon of modernism. The reason I planted it there is because this famous tautology is deeply rooted in the linguistic memory of English, and it captures the arbitrariness of language that Marcelo is questioning in the story. For Stein, repeating a word over and over gradually breaks the bond of word and reference.

KD: So, in the original Brazilian Portuguese text, that phrasing “a rose is a rose is a rose” doesn’t exist?

TG: No, it’s not in the Portuguese. Ruth Rocha is working with Brazilian sounds and references, and I had to do something else. There’s a well-known image by Nikolai Trubetzkoy in which he says that each language is like a fishing net: when it is cast it captures certain kinds of experience while letting others slip through.

KD: Did you have any interaction with Ruth Rocha as you were preparing the translation?

TG: I actually sent her my translation for her approval. She, her sister and her agent read it and approved it. There are lots of translators who prefer their authors dead. Ruth Rocha could have said, “Oh, no, I hate it!” But she was in her nineties and delighted that Marcelo was getting an afterlife in English.

When Yael Bernstein at Tapioca Press decided to publish it, she commissioned Ana Matsusaki to do the illustrations, which followed the new translation.

KD: What are some changes in the illustrations that mirror the linguistic shifts?

TG: I’m often asked whether all these marshmallows in the English version, with Ana Matsusaki’s rich layered visual storytelling, grew out of the original Portuguese. The answer is no. The original title in Portuguese is Marcelo, Martelo, Marmelo. Marmelo is a type of fruit in Portuguese (quince fruit). Texts travel in very interesting ways across different times and languages; they gather new connotations, accumulate historical layers. In English, marshmallow is playful and sticky; belongs to the world of children, sounds, mouths and memory. It fits Marcelo’s linguistic curiosity. His absurd question, why not marshmallow? is a search for rhythm and taste in another tongue.

Also, in the original there’s Martelo (spelled with one l), which in Portuguese means hammer. I added a second ‘l’ so that Portuguese martelo became English martello (with two l’s), meaning little tower – and the illustrations reflect that too, among other things.

KD: Can you give some historical reference for the original Marcelo?

TG: Marcelo is a book of the 1970s, a very important period in Brazilian literature because it was a rupture from more moralistic, didactic literature. Children suddenly had agency; they experienced things and could ask questions. During the 70s there was the dictatorship in Brazil, and with that came censorship. However, children’s books were overlooked. So many of the very important authors, like Chico Buarque, who didn’t normally write for kids, wrote children’s books as a way to circumvent censorship.

KD: I like that Marcelo is this child who’s asking questions and essentially questioning the norm, which represents an attitude and spirit felt during 1970s Brazil.

TG: He asks, why don’t words make more sense? For him language is inappropriate, full of flaws and incongruities, a kind of disaster. Marcelo wants a more rational language, a better-designed language. And so he decides he will invent his own language. There are thousands of invented languages which, as a linguist, I find fascinating. I’d love to work on a picturebook inspired by the American linguist Suzette Haden Elgin, who in the 70’s created a whole new language called Láadan because she thought the English language was inadequate to express emotions that had to do with women’s experiences. There are many things we’d like to say that often seem impossible to put into words. Láadan was constructed as a language attuned to sensitivity. Imagine the princess of The Princess and the Pea turned into a linguist in pursuit of her peas.

You mentioned norms, and translators of children’s literature often have to navigate and negotiate multiple socio-historical norms. Every period and cultural context has its own specific expectations and constraints about what is and what isn’t to be translated, about how to translate, about what counts as “children’s literature” and also about how “childhood” is imagined and defined. I think one of the privileges of being able to choose what you want to translate is the possibility of pushing a little bit against those norms and expanding their limits.

KD: At one point Marcelo’s parents just decide to go along with their son’s new language. They learn the language to create a bridge to their son, to shorten the divide.

TG: Yes, in a sense they translate themselves to connect and interact with him. That idea is also at the heart of a broader initiative my students and I at the University of Massachusetts Amherst have been developing over the past few years in partnership with the Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art. The Pipa Project explores translation as a social relation where collaboration and interaction are central. We translate children’s books into English, design multilingual storytelling programs that are then shared with the community at the museum. Within this framework, translation does not begin and end on the page. Orality plays a crucial role, and translation is explored, above all, as a form of interaction.

KD: How did this project arise?

TG: My father died of COVID in 2021. My way of mourning him was actually going back to the children’s stories in various languages we had shared over the years. I started translating some of them. It became a particular kind of ongoing memorial.

When I went back to school at UMass, I suggested to students that we try something similar in class. Being in Massachusetts, where there are large Spanish- and Portuguese-speaking communities, many of my students are heritage speakers. They brought with them memories of the books they had heard as children, the translation process itself involved a moving intergenerational dialogue between the students and their families. Many of the students’ families came to the performances at the Eric Carle Museum. It was a powerful experience. Over time, the project expanded to include additional languages as well.

Since then, we’ve translated and led many storytelling sessions at the Eric Carle Museum, involving more than 200 undergraduate and graduate students. Out of this work grew a full course called Community, Storytelling, Translation which I now teach at UMass every two years. Last Fall we presented an entire series at the museum called Stories in Your Language and Mine. Students chose a picturebook and designed it for bilingual storytelling, working closely in workshops with the museum’s literacy director, David Feinstein.

Guimaraes Rosa, the great Brazilian writer, famously said “traduzir é conviver”: to translate is to live with, to be with, to dwell with. I take that phrase as the guiding principle of this community engagement project. The translation of children’s literature, in this context, becomes an open-ended, shared experience across multiple differences.

To learn more about Tal’s translation and multilingual storytelling project at the Eric Carle Museum, see this video, which includes excerpts from several presentations made at the Museum.

Tal Goldfajn

Tal Goldfajn is a linguist, translation scholar, and translator. She is an Assistant Professor in the Spanish and Portuguese Program in the Department of Languages, Literatures, and Cultures at UMass Amherst. She is working on a book titled Translation and Inheritance, for the Routledge series New Perspectives in Translation and Interpreting Studies. Her most recent English translation, Marcelo, Martello, Marshmallow by Ruth Rocha (Tapioca Stories), was selected by USBBY as a 2025 Outstanding International Book.

Katy Dycus

Katy Dycus works for an academic department of anthropology and serves as co-editor of the World Kid Lit blog. She has reviewed literature in translation for Harvard Review and Words Without Borders, and her essays appear in Appalachia and Hektoen International, among others.

World Kid Lit is a nonprofit that aims to bring diverse, inclusive, global literature into the hands and onto the bookshelves of young people. We rely on grants and donations to support our work. If you can, please support us at Ko-fi. Thanks!

We earn a small commission every time you buy books via the affiliate links on our site, or via our booklists at UK Bookshop.org. This is a much appreciated donation towards our work. Thank you!