By Claire Storey

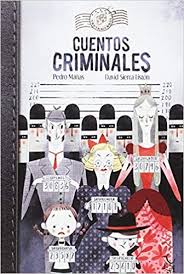

Yesterday, we introduced you to Spanish children’s book Cuentos Criminales by Pedro Mañas and David Sierra Listón. Today, we’re discussing one of the challenges involved when taking a book from one culture and presenting it in another: bad language. Often, swearing is more acceptable in one language and cultural situation than another, not only in the force and choice of words, but also whether cursing is considered appropriate at all.

Yesterday, we introduced you to Spanish children’s book Cuentos Criminales by Pedro Mañas and David Sierra Listón. Today, we’re discussing one of the challenges involved when taking a book from one culture and presenting it in another: bad language. Often, swearing is more acceptable in one language and cultural situation than another, not only in the force and choice of words, but also whether cursing is considered appropriate at all.

When I translated an excerpt of Cuentos Criminales for my Master’s Degree, not only did I have to come up with a translation solution, but I also had to be able to justify my reasons for my solutions. Let’s look at a specific example.

In the book, Inspector Archibald Wilson describes how his uncle lost the family fortune by investing the money in a company making candelabras shortly before the invention of the light bulb. In the Spanish, he exclaims:

Lo perdimos todo, maldita sea.

One possible translation of this would be:

We lost it all, goddammit.

While in Spanish, the word maldito and its variations are used freely for this age group, a question mark remained in my mind as to whether damn and its English variations would be acceptable in an English-language book aimed at children aged nine to twelve. I had to have concrete reasoning.

To find out what English speakers thought about damn, I carried out an online survey asking what people thought about the use of damn and goddammit. Overall, the majority of responders answered that they thought damn was acceptable; however, over a third of responders didn’t agree. For goddammit, over half responded that this was not acceptable.

A discussion on Twitter involving translators Ruth Ahmedzai Kemp and Katy Derbyshire also concluded that while the translator may be likely to leave mild swear words in their translations, more often than not, UK editors would often take them out. I wondered why this was.

When thinking about who buys and reads children’s books, it’s often an adult that buys a book for a child, so creating a “dual audience” (Wall in Oitinnen, 2006, p. 35). Those adults who don’t find damn acceptable may censor their children’s reading, either by not allowing their child to read books containing the word or by changing the words if reading out loud. On Twitter, freelance children’s publishing consultant Lisa Davis supported this idea, giving the following advice: “I’d avoid ‘damn’ entirely because some adults will find it problematic in a children’s book.”

I also discovered that in January 2019, the Head Teacher of my children’s school removed two books from its year 5 and 6 reading challenge list due to “bad language”. This wasn’t as a result of complaints by parents but rather down to what is regarded as “appropriate” for children to read.

It was becoming clear I needed to avoid damn. But I wasn’t the first translator to be faced with this issue, so how had other translators dealt with this issue?

In The Treasure of Barracuda, the English translation of Llanos Campos’ pirate adventure El Tesoro de Barracuda (2014), Lawrence Schimel translates maldito differently every time it appears:

| malditos pescadores de agua dulce | blasted freshwater fishermen |

| maldita sea mi suerte negra | my rotten bad luck |

| el maldito viejo | crazy old codger |

Whether consciously or not, Schimel avoids “bad language” and in doing so becomes far more creative in his solutions – I particularly love the last one!

If we return then to our original phrase (We lost it all, goddammit), some options I considered included “for goodness sake”, “for Pete’s sake”, “by golly”, “blast it” and “darn it”. But none of these seemed to fit with the rest of the sentence. I then decided to play with the sentence structure, disregarding “maldita sea” as an additional expression, and trying to think more creatively. I also took inspiration from other books, in this case the book Quackers by Moon (2002), a levelled book for UK Key Stage 2, the corresponding age group for this text.

This led me to change the sentence structure, omitting the end expression but including the euphemism “flipping” in the middle of the sentence to read:

We lost the whole flipping lot!

This retains the feeling of distaste at having lost the money while being more appropriate for the age group. It is also quite a funny expression which ties in with the overall humorous tone of the book.

While translators cannot be expected to carry out this sort of research for each individual sentence or challenge, it is interesting to follow a thought process to see why we translate in certain ways.

Claire Storey is a literary translator based in the UK. She works from German and Spanish into English and has a particular passion for children’s books. In 2019, she received a Special Commendation from the Institute of Translation and Interpreting in the ITI Awards category for Best Newcomer. She also enjoys sharing her love of languages and books with anyone who will listen!

The threshold of swearing in Spanish is indeed much wider, particularly concerning children. My MA dissertation was on children’s literature so I’m well aware of the issues you raise in your post. I have the advantage of having worked with children in the UK for 23 years so I feel more confident in knowing what’s appropriate. I would never use ‘damn’ for that age group. I’d consider it for older teenagers. Translating for children is much more complicated than people may think. The challenges of writing for a dual audience and breaking the cultural barriers seamlessly; children don’t care if it’s a translation; they just want to read a book that engages them and resonates with them.

In my work I focused in wordplay and onomatopoeia. Another two important challenges when translating anything but particularly common for n children’s literature. How did you deal with that?

LikeLike

Hi Pilar, Thanks for your comments. I agree about most kids not caring if it’s in translation. They just look at a book as a book. I have a 9-year-old son and it was really interesting talking to other parents on the playground about their views. I think in the end most people were agreed that “damn” as an expression (Damn, I hurt my foot!) wasn’t too bad but using it towards someone else, like “damn you!” was really not acceptable. And while I was already aware of the higher frequency of swearing in Spanish, to actually have to find evidence was a useful exercise.

Regarding onomatopoeia, it would be interesting to hear what others have to say, but I would suggest you have to find the solution that fits in your target language, unless you’re trying to give a flavour of the source. There are lots of discussions out there about the different sounds animals make in different languages – woof woof, guau guau. One that came up in this particular translation was a pair of scissors that went chack chack in Spanish. In English scissors go snip snip so that was the obvious solution.

For the wordplay in this translation, as I mentioned in my post yesterday about the book, there is a whole section where the characters “mispronounce” words because of issues with their teeth – it adds a whole new level of humour to the text! I spent a lot of time talking to myself and listening to my kids and their friends (especially if their teeth had started to fall out!). From there I was able to work out what sounds would be affected in English and apply the “mispronunciations” to my translation. Sometimes I had to rewrite sections of my translation because my first version didn’t include any of the letters I needed to include. Without the wordplay, the text wasn’t funny anymore, so that had to be the priority.

If you’d like to discuss further, feel free to drop me an email 🙂

Thanks, Claire

LikeLike

[…] 18 Sept ‘Damn!’ and Other Translation Conundrums […]

LikeLike