Literary translator Mercedes Guhl tells us about her wealth of experience translating children’s books from English into Spanish, and about the books of her childhood in Colombia…

How did you get into translating children’s books? What would you have done differently looking back?

After 30 years of working with books, I don’t think I have regrets about how all of it started. My first translation was a picture book. It was a test to enter my first job at a publishing house, when I was at the end of my last year in college. After that, every project I had as junior editor of children’s books was checked and supervised at least by two superiors who gave me feedback and corrections. I learned a lot from that. After two years I quit, in order to become a freelance book translator as I discovered it was my favorite part of the editorial process.

What have been the most helpful resources or events for you that have helped you navigate the world of children’s books and publishing?

The most helpful resource for understanding the world of children’s books and publishing was actually working at a publishing house, and getting to be close to all the processes of producing a book in translation, from rights negotiation to the freshly printed book ready to go to bookstores.

Besides that, I attended workshops and courses within book fairs or conferences, with people working in book promotion agencies, libraries, and other publishers. All that certainly helped to explore the world of children’s books in terms of background, history, and the actual making of them.

Which books from Colombia or authors writing in Spanish would you love to see translated into English?

There are several interesting authors I can think of. Some of them rejoice in language and images, and move around mostly poetic fields, like Alekos. Others are fascinated with Colombian nature and landscape, turning it into an important presence in their books, like Celso Román. Irene Vasco combines language, imagination, and local color. And there are those who work on more complex worlds and narratives, interweaving imagination, real events, the violent clash between rural and urban Colombia, and some coming of age experience, like Triunfo Arciniegas, Jairo Buitrago and Yolanda Reyes.

Were there any translated children’s books you loved as a kid, and were you aware of translation or that they came from a different place? Do you think it matters that young people have access to books from beyond their own country or region, and why?

There were very few Colombian children’s books in my childhood. We read and heard the same Western folktales that my grandparents’ generation may have read in Colombia and other countries: the Grimm brothers, Charles Perrault, and also fables, from Aesopus to the Spanish Iriarte and Samaniego. As I grew older, other books came to my life: Enid Blyton, Jules Verne, Michael Ende’s Momo, my favorite book for several years, along with Little Women. I didn’t care if they were translations. I think you are in search of different things when you read and not the same reality that’s around you.

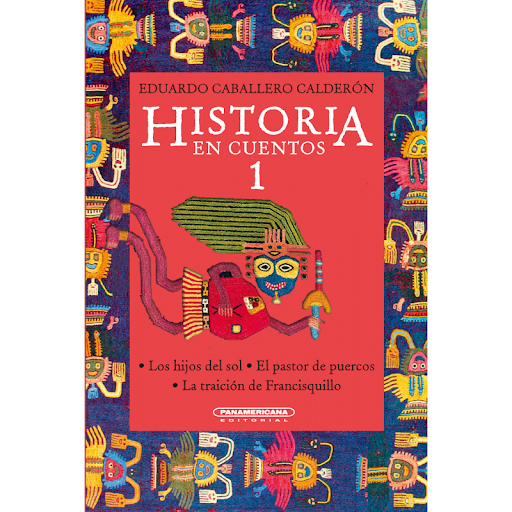

But even my favorite Colombian books meant looking into a different reality. La historia en cuentos, by Eduardo Caballero Calderón, a series of historic anecdotes developed into children stories, stretching from pre-Columbian times to Independence, was published in the 1970s, and became one of my favorite readings, despite showing me a world 400 or 200 years before my times. And a short novel that I don’t think has been reprinted since the 1970s, El documento by María Fornaguera, was the first book I came across that dealt with guerrilla and warfare in the country and it really shook me to core.

What is your favourite children’s or YA book that you have translated from English into Spanish? Were there any particular challenges in that text and how did you overcome them?

I think the books I have enjoyed translating the most are not exactly the best ones but those that have meant to plan and ponder a translation strategy that doesn’t come very straightforward, in order to deal with a particular feature of the text like word play or cultural references. I have a story of love-hate with Canterville’s Ghost, as I felt I wasn’t doing a good job in differentiating speech traits of Brits and Americans in dialogues, but years after that translation was finished I bumped into the father of two kids who had relished that book, after having read another translation that just didn’t do it for them. In 2018 I translated Holly Goldberg Sloan’s Short, and it entailed two interesting challenges: careful work with language, for recreating the dialogue that had the format of a play; and careful research into The Wizard of Oz in its various forms, book, movie and musical.

6. You translate into Spanish for publishers in Colombia, Mexico, Dominican Republic and the US. How conscious are you of modifying your Spanish for different regional audiences? Is it something you do before submitting a text or is that the role of the editor? Do tell us anything interesting about the challenges of working into a language with such regional differences!

My approach to translating books that will be read all over Latin America is to use a type of language that I have called “translucid Spanish” for my courses and workshops. I don’t think translators should translate into their peculiar and personal language but construe one that reflects the author’s language. Regional differences mean we use different terms for the same thing, but that doesn’t mean we cannot understand each other. There are some local terms that are more understandable than others. Those are translucid Spanish terms, because it doesn’t matter if the translator and the reader use them in their daily life, but they sure can understand them. There are opaque regional terms, that someone who is not from that region will not get, or that can be ambivalent. I also try not to use terms that are clearly marked as belonging to a very particular region. All this entails getting closer to regional varieties, reading authors/translators from other corners of the Spanish-speaking world, getting to know the terms that TV programs have transformed into common currency for all Spanish-speakers, and searching linguistic corpuses. Those are elements of my translation toolkit, but I have to say that intuition also plays a big role in the process.

***

Mercedes Guhl is an English to Spanish literary translator with over 80 published translations. She also has gone into teaching, training translators at undergraduate and graduate levels, in Colombia and Mexico. For several years between 2008 and 2018, she organized the annual conference of the Mexican Translators Organization. She currently serves as Administrator of the American Translators Association’s Literary Division.