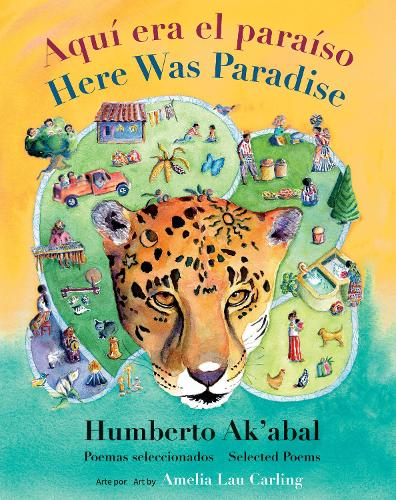

In August 2021, Groundwood Books released a new bilingual poetry anthology by celebrated Guatemalan Indigenous poet Humberto Ak’abal. World Kid Lit caught up with translator Hugh Hazelton to find out more…

World Kid Lit: Congratulations on the publication of Aquí era el paraíso / Here Was Paradise by Humberto Ak’abal. Could you introduce the book and the author for us?

Hugh Hazelton: Humberto Ak’abal, who passed away three years ago, was an outstanding poet in both Indigenous and Spanish-American literature. He was born and spent most of his life in the village of Momostenango, in the western highlands of Guatemala, though he also lived for a while in Guatemala City when he was young, and later in life travelled to literary conferences, festivals and readings all over the world. Ak’abal published twenty-one books of poetry, four collections of short stories and five books of essays, including a retelling of the Popol Wuj, the foundational narrative of the K’iche’ people. Patricia Aldana, who was born and grew up in Guatemala and was the founder of Groundwood Books, has long admired Ak’abal’s work and wanted to make a selection of his poems about life in his village.

WKL: The collection is published as a bilingual edition in Spanish and English. Was it always the plan to publish the collection in a bilingual format? With the text displayed immediately side by side, does this have an impact on your translation process and if so, how does it differ to a non-bilingual edition?

HH: Ak’abal always preferred to write his poetry in K’iche’, since it was his mother tongue and he wanted his people to have full access to his work. He would then self-translate it into Spanish so that it could also be understood in the Hispanic and other literary worlds. Eventually his work was translated into thirty languages, and he became the most celebrated poet of Guatemala. The bilingual format permits readers of the two languages to compare the texts and puts a certain pressure on the translator to follow the source text more closely, especially if there’s a sizeable bilingual readership. In unilingual translations, the translator can take more liberties, if he or she wishes, since few readers will ever compare it with the original.

WKL: Humberto Ak’abal originally wrote these poems in the Indigenous Maya K’iche’ language from Guatemala before he self-translated them into Spanish. Does this change your approach to the translation, or do you approach the text as you would any other poems written in Spanish?

HH: Ak’abal’s poems are so beautiful and unique in style and so deeply rooted in Indigenous ways of perception and being that it was a delight to continue on with a second layer of translation, rendering them from Spanish into English. Like many poets who self-translate, he felt at liberty to find interesting ways to keep or even amplify the original within the framework of the second language, so long as the two were parallel. Since I was translating his work, though, rather than my own, I felt that I should be more careful and faithful to the Spanish, though I did make a few of my own adjustments in order to bring out the essence of the text. When translating the work of Indigenous authors, it’s important to try to convey the characteristics of the original language, including the wording, rhythm and musicality of the text, even if they occur in or underlie a subsequent translation into a European language. I did have some experience in this trace effect from working with Mexican Indigenous writers at the residence program in the Banff International Literary Translation Centre for a number of years, as well as from revising French to English translations of poems and short stories by Indigenous writers for an anthology of Canadian Indigenous writing for the Banff Centre Press.

WKL: Ak’abal sadly passed away in 2019. Were there any moments when you were translating his poetry where you thought, “I wish I could ask him this!” and how did you work to resolve any of those issues?

HH: Yes, I would have deeply enjoyed being able to talk about the work and discuss different terms and expressions with him. I had met him in 2012, when we both read at the annual Festival de Poesía Las Lenguas Carlos Montemayor in Mexico City, which included eight Indigenous poets from all around the Americas and one poet in each of the European languages of the hemisphere (Spanish, Portuguese, English and French). It’s a weeklong affair that includes interviews, roundtable discussions, various soirées and one final major reading in the Sala Nezahualcóyotl of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), which has over two thousand seats. Humberto’s readings, in which he would periodically break into birdcalls, were superb. All of us were in the same hotel, and often talked together during our meals and in the evening. It was a marvellous chance for me to get to know Humberto, as well as other Indigenous writers from Guatemala, Mexico, Ecuador and Colombia, many of whom knew each other from past readings around the world. Years later I came across an extensive interview with Humberto, in which he remarked that “onomatopoeia is an integral part of the K’iche’ language. You can say much more with sounds than by trying to explain something,” and added that “sound intersperses music within language.”1

WKL: The poems in the collection are beautiful both in Spanish and English. I really love the imagery of nature. A couple of my favourites are “Cantos de pájaros” / “Bird Songs” and “Piedras” /” Stones”. Do you have a favourite?

HH: Nature is an integral part of Humberto’s poetry, because that’s the world in which he lived. Translating this book was such a profound pleasure that I just immersed myself in his words and descriptions, which were always vivid and concise, leaving echoes of serenity. The cascading selection of subjects from nature and village life was like a day or a lifetime spent there with the author, and I loved them all, from the birds and insects to the water, forest, harvest, nightfall and ghosts. Who else could write such a perfect poem about stones: “It’s not that the stones are mute: they just keep quiet.” Everything in nature is alive.

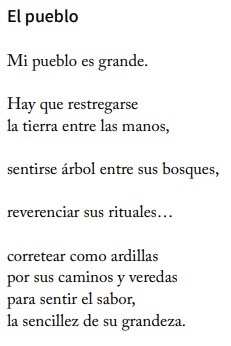

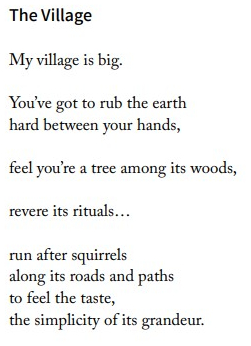

“El pueblo / The Village” from Aquí era el paraíso / Here was paradise : selected poems of Humberto Ak’abal, selected by Patricia Aldana, copyright © 2002, 2006, 2013 by Humberto Ak’abal. English translation copyright © 2021 by Hugh Hazelton.

Reproduced with permission from Groundwood Books, Toronto

WKL: You have won numerous awards for your translations. What are the main differences between translating for adults and translating for children?

HH: The differences depend on the text. When I was translating this book, for instance, I wasn’t really conscious of it being for children or adults, because it’s understandable for both. Ak’abal believed that “The child’s vision is forever present among the adult’s words.”2 Other books for young readers that I’ve translated, though, such as A Small Nativity, which I did for Groundwood in 2007, had a pronounced lyrical rhythm and rime that I had to adapt to English by rearranging the order of the words, since metre is different in Spanish and rime is much more common.

WKL: More generally, how did you get into translating poetry and do you have any top tips for anyone wanting to do it?

HH: I write poetry myself, and have often translated my own work into French and Spanish for readings here in Montreal. Since I was active in the Latin American community, my friends would ask me to translate their work for events, grants or publication, and I ended up translating a number of books of poetry by Latino-Canadian writers from across the country. I also taught Spanish translation at Concordia University and would often use translations of work by local authors with my students. At the same time I continued to explore and translate Quebec and Haitian poetry. For many years I worked with Ruptures: la revue des Trois Amériques, a journal which published poetry and prose in all four European languages of the Americas, complete with translation. The last few years have seen a boom in interest in literary translation in North America, with many new university programs and translation reviews. It’s a perfect moment for new translators of poetry to enter the profession. To do so, they’ll have to find the right balance between how closely to follow the text and how often to reach out beyond the literal meaning of words to convey the true message of the work.

***

References

1 Ollé, Marie Louise. “Entretien avec Humberto Ak’abal,” in C.M.H.L.B. Caravelle 82, Toulouse, 2004. 205-223. p. 219.

2 Ibid. p. 221.

***

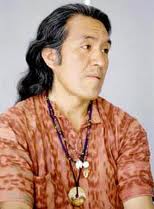

Photo credit: Edith Boucher

Hugh Hazelton is a writer and translator who specializes in the comparison of Canadian and Quebec literatures with those of Latin America, as well as in the work of Latin American writers of Canada. He has written four books of poetry and translates from French, Spanish, and Portuguese into English; his translation of Vétiver (Signature, 2005), a book of poems by Joël Des Rosiers, won the Governor General’s award for French-English translation in 2006. He is a professor emeritus of Spanish at Concordia University in Montreal and former co-director of the Banff International Literary Translation Centre in Alberta.