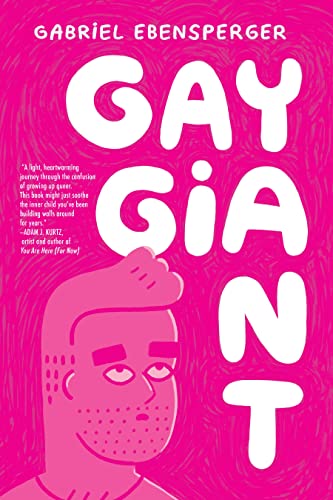

World Kid Lit blog co-editor Jackie Friedman Mighdoll speaks with the translators Kelley D. Salas and Mercedes Guhl about their work on the recent Chilean graphic novel memoir Gay Giant by Gabriel Ebensperger published by Street Noise Books in 2022...

World Kid Lit: Gay Giant is such a fun and poignant read. Can you tell us how you came to work on this project?

Kelley D. Salas: A few months before the 2019 ALTA conference, I was looking for something to pitch to Words Without Borders. They have an annual Queer issue and also an annual graphic novel issue, so when I came across this graphic memoir about growing up gay in Chile, I thought it might interest them. At the time, Mercedes was mentoring me in a one-year program through the American Translators Association. She gave me feedback on the excerpt and helped me practice my pitch before the conference. About a year after Words Without Borders published the excerpt, Liz Frances of Street Noise Books contacted me on LinkedIn to see if I’d be interested in translating the full book, and it seemed like a natural fit to ask Mercedes to work on it with me.

WKL: This is a coming-of-age story about a gay boy in Chile. That’s far away from your own life experiences, I’d imagine! How do you approach the text in this case? How did you find the voice? Were there any special challenges?

KDS: It is far from my own experiences, but the author’s journey toward self-acceptance really struck a chord with me. And sadly, the homophobia Gabriel describes felt quite familiar—those kinds of taunts and slurs were rampant in my high school in the 80s. Gabriel takes a lighthearted tone, though; he’s funny and ironic and sarcastic. The US cultural references were not too difficult, because I knew most of them, but the most challenging parts for me were the references to Latin American performers and songs and shows. How do we convey meaning in the English translation, when so much of the cultural shorthand in the Spanish version won’t mean anything to most US readers?

MG: I don’t think a translator needs to feel identified with a character for translating a book, but I always try to understand characters and situations and imagine what they would be if I experienced them. It’s a bit like the work actors do in playing their part. If there are points in common with any of the characters, like the songs, performers and shows mentioned in this book, then things get easier to imagine.

WKL: Part of the great fun of this book for me was reading all those cultural references. They seemed so universal—or were any of those changed in the translation process?

KDS: They were changed! For each reference, we had to decide whether to adapt it, contextualize it, leave it as is, or (in very few cases) omit it. Often, we adapted by finding an equivalent reference that US readers would understand, like substituting Cher for performers like Yuri and Rafaella Carrá, or using Diana Ross’s “I’m Coming Out” in place of a song by the (Spanish trio) Mecano that would be totally unknown in the US.

MG: Sometimes you find a good match for a cultural reference, like the ones Kelley mentions, but others are more problematic. Juan Gabriel, the Mexican musician and performer, was one of the latter. We needed a sort of equivalent sporting colorful flashy clothes, eyeliner (and later notorious face lifts), songs about love and despair, and a certain androgynous quality. Prince was one of the options that jumped into my mind, although in a different music genre, but for a while I thought it could work. I suggested this option to Kelley and we decided to sleep on it. When you’re stuck with a problem like this one, it’s always good to get more opinions. A fellow Mexican translator suggested Liberace, or even Elvis Presley. In the end, this was the kind of controversial translation choice that required input from the author and editor. I don’t think you can fully equate Latin American cultural icons and US ones. They went for a sort of adaptative translation to reach some level of understanding, using as leverage the continuous flow of US cultural icons into Latin America: the reference to “JuanGa” remains in the book in English but his personality and impact are conveyed by means of comparing him to both Liberace and Elvis.

WKL: I’m always curious about how different collaborations work. Can you tell us more about your process?

KDS: For this book, I drafted everything, and then Mercedes would read my draft and we’d meet on Zoom to discuss what she calls the cultural “baches”—the difficult spots. We’d figure out solutions to most issues during the calls, but then certain things, like the Juan Gabriel reference, needed time to percolate. For days, we’d each go about our other work with those problems nagging at us in the background. We had some funny aha moments when one or the other of us would suddenly think of a solution and reach out to the other via Whatsapp or email to propose it.

MG: As English is not my mother tongue, I can’t really “correct” a translation into English, but I can tell if an important aspect of the original meaning gets lost in the translation or if the tone and register are similar. When Kelley gave me her draft, I would first try to understand how and why she made her translation decisions. Once I understood her approach, I could get a clearer idea of the spots that needed reworking. As a Colombian who’s been in touch with other parts of Latin America, I could act as some sort of cultural consultant, explaining bits in the story so that Kelley’s translation was more accurate and to the point. Then we’d each offer options and suggestions for those difficult spots, until we reached a decision. The conversations Kelley describes were fun and challenging, and it’s great to see a good solution coming out of all that.

WKL: The visual representation of the text is also important in this story given that it’s a graphic novel. Did you have limitations in terms of how many characters or where the text would go? How did you approach this added constraint?

MG: For graphic genres, the translation has to include not just the text, but also the page number, frame number, and speech balloon number for each line of text, so that the letterer can easily place the text into the book. And there are space limitations—the text must fit the given space. You can rephrase sentences and lines to make them more compact, or use synonyms to keep a similar text length. In this project, we were lucky the author/illustrator did the lettering, so he could make slight changes to the visuals, like enlarging speech balloons or filling them with smaller letters so that a longer text could fit in. But this doesn’t always happen.

WKL: I find each project that I work on teaches me something big – either about craft or the business or myself! What do you think you carry forward with you from this project?

KDS: One big takeaway for me is that collaboration is powerful, and I want to do more of it. Every time I’ve had the opportunity to work with others on my translations—whether on a book like this, or in a space like our Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators (SCBWI) translation critique group—the end result is better for it.

MG: I find it fascinating to read other people’s translations, because it gives me a glimpse into how their minds work and the way they decode a text. And when those translations are still in the making, there is room for discussion and improvement. After collaborating on this project and on a couple other graphic novels into English, I have realized the importance of having a cultural consultant who can shed light on cultural bumps and linguistic peculiarities. Collaboration is powerful, indeed! And when you are a seasoned translator like me, there’s always something to learn from fresh minds!

WKL: Do you have any suggestions or advice to emerging translators?

KDS: I’m still emerging myself, hoping to get out of the place that Anton Hur refers to as the “Translator Valley of Death,” where you’ve published one book translation and you’re trying to get a second. There are two pieces of advice I’ve heard that I try to follow. One: read a ton. And two: pitch, submit, and move on to the next project.

MG: At the start of my career, in my twenties, an editor told me I could only become a good literary translator once I was older than forty. It was such an enraging comment! As the years have gone by, I think I understand what he meant. Reading in your target language is a great way to stock up your linguistic and stylistic toolbox and enrich your repertoire of narrative voices. Writing and editing texts allow you to practice using those tools.

WKL: What’s next for you? Anything else you’d like to share with our readers?

KDS: I have a bunch of different projects that I’m submitting to various publishers: a picture book, a YA graphic novel, and a YA novel—and a couple other things for adults, too. And I’m open to working with other translators, editors, and publishers.

MG: I already have a couple of book translations in the queue for next year, and I would like to turn a bunch of scribbles and notes into an essay or series of short essays about translating, from the point of view of someone who works for the publishing industry and learns to love each book as some sort of short-lived arranged marriage.