Following on from #WorldKidLitMonth, our guest co-editor Charlotte Graver signs off with this wonderfully insightful interview with Alice Curry, the founder and CEO of UK-based publishing house, Lantana Publishing...

Charlotte Graver: Hello and welcome back to the World Kid Lit blog. Thank you so much for taking the time to talk to us today. Could you firstly start by telling us a bit about Lantana Publishing? How did it come about and what is its mission?

Alice Curry: Hello and thanks for having us! I founded Lantana in 2014 so we’ll be celebrating our 10th anniversary next year. I had previously worked as a university lecturer in children’s literature and had become increasingly aware of the gaps in children’s publishing, particularly when it came to racial and ethnic representation in children’s books. Some voices were being heard, but many were being ignored or lost. Soon this gap became almost impossible to ignore – as CLPE found when they undertook their landmark Reflecting Realities survey a few years later*.

This realisation coincided with my sister marrying a man whose parents had emigrated from Hong Kong. With the prospect of mixed-race nephews and nieces on the way – of whom I now have three! – I was determined to find a way for them to grow up reading books in which they could see themselves reflected. Hence Lantana was born, and its mission to publish inclusive books has expanded beyond race and ethnicity to include all under-represented groups over the past few years.

CG: It’s such a wonderful mission and I love how your name reflects this with lantana flowers all holding different colours on one stem. Did you always know that this would be your name?

AC: I lived in Australia for many years where the lantana flower is a common sight and I’ve always loved the spread of colours on each stem. When I moved back to the UK and founded Lantana, the flower stayed with me and it felt like a fitting emblem for everything I wanted to achieve with my new press.

CG: As you outline, you want to publish books for all children. Do you have a particular age range or genre that you like to centre upon?

AC: Picture books for young readers aged 2+ have been our heartland since the beginning, and we’ve had particular success with picture books that veer towards the older reader of 6+ and can be used by teachers in the classroom. We’ve also recently started publishing illustrated early fiction for readers aged 7-9 and middle grade chapter books for readers aged 8-12 which we’ve been enjoying, and we’ve seen some surprising successes with a few non-fiction titles for age 7+, particularly in the United States where they’ve been purchased in large numbers by state-wide education bodies like the New York Department of Education.

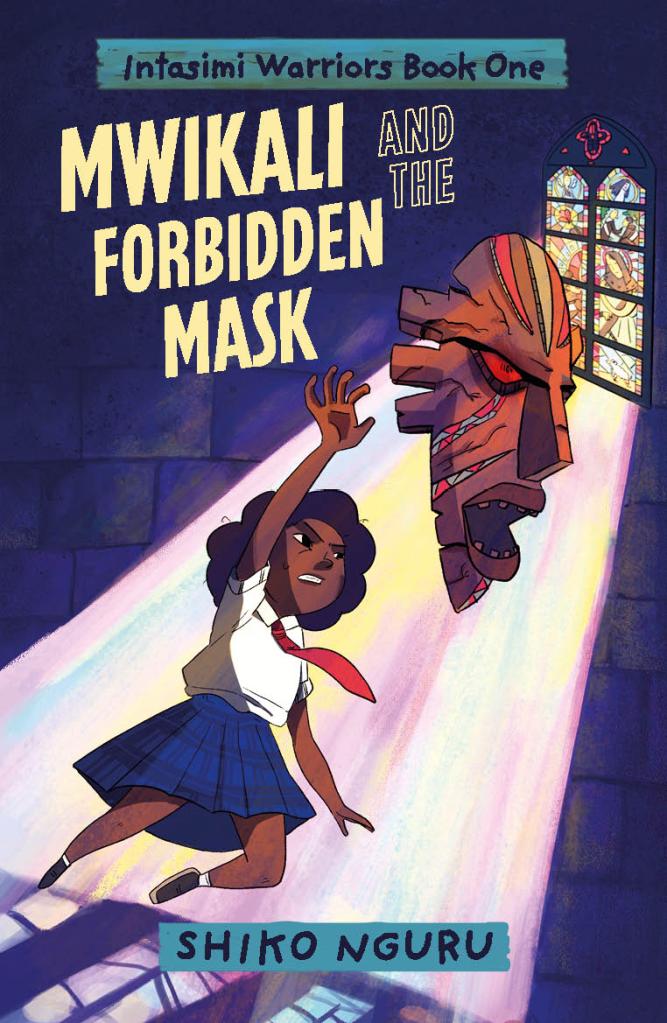

Lantana Publishing’s first

Middle Grade novel

CG: How have you found branching into middle grade fiction? Are there different challenges that come from publishing books for different ages?

AC: We’ve really enjoyed the challenge of publishing for older readers. It definitely takes a different process and a different set of skills than picture books, and of course there will be some material which is age-appropriate for one set of readers and not for another, but in essence, the practice of creating all our books is the same in that it starts with telling a great story, and everything else flows from there.

CG: I love the sound of titles such as the Intasimi Warriors series. I also love how many translated titles there are in your catalogue. Given that your mission is to publish ‘inclusive books’ from authors ‘around the world’, did you always know that translated fiction would be a big part of your catalogue?

AC: Before founding Lantana, I had undertaken some long-term freelance work for a charity focused on improving education across the Commonwealth where English is at least one of sometimes many national languages, so my initial focus was on English-language titles by authors living around the world and particularly in the global south.

Our early titles reflect this – Chicken in the Kitchen by Nigerian American author Nnedi Okorafor, Sleep Well, Siba and Saba by Ugandan author Nansubuga Nagadya Isdahl and so on. However, I’ve always loved reading in translation so it was a natural next step for us to move into translated titles.

CG: Could you tell us a bit more about what type of things you look for in your titles?

AC: We’re really interested in the lived experiences of authors and illustrators from minority groups. Our publishing tends to fall into two categories – local and global. Our local books explore the world through the eyes of characters from under-represented groups – a mixed-race child growing up at the intersection of two cultures, a young boy with two mums, a girl learning to cope with her mother’s hearing loss. Our global books, on the other hand, explore countries and cultures beyond our borders – a child celebrating the New Yam Festival in Nigeria, a young boy living in war-torn Syria, a shopkeeper teaching a young girl how to read in a Colombian pueblo.

CG: I’m aware that you accept submissions for manuscripts and book dummies. Is this the way in which you find the majority of your titles?

AC: Yes, despite the many, many hours of reading it entails, we’ve always valued our open submissions policy. We’re really happy to work with un-agented and debut authors, particularly those who feel they aren’t finding representation within the mainstream book trade. I would say that on average we discover around half of our titles through the slush pile. The rest come from agents, previous authors we’ve worked with, international acquisitions, and on rare occasions, our team reaching out to authors directly.

CG: I think it’s great that you have an open call for submissions and that you work with so many un-agented and debut authors. Could you talk a bit more about the submission process?

AC: We’ve recently seen an uptick in translators submitting titles they’d love to translate to our slush pile and I’m really pleased to see this. We love discovering new international titles this way and will review them in the same way we would a normal manuscript. The only difficulty is that we can only expect a translator to submit up to three chapters of the novel in question rather than the full manuscript/book dummy we insist on for authors and author-illustrators. This does make evaluating the proposal harder, however, if the submission is well supported by a summary document and information on the book’s reception in its home country, as well as details of which publishing house to contact to secure English-language rights should we choose to move forwards with it, then that’s a very good start.

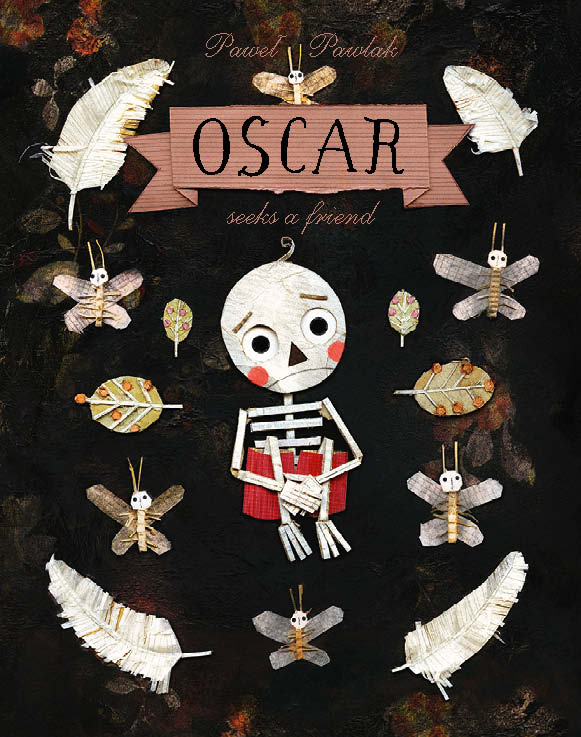

CG: That’s really interesting what you say about difficulties in evaluating translation proposals. Do you find that there tend to be more obstacles to overcome when publishing translated titles? I know when World Kid Lit spoke with you about Oscar seeks a friend you mentioned how important funding from the POLAND Translation Programme was. Is funding perhaps one of these obstacles for translated titles?

AC: Funding is very much an issue for longer-form fiction where translation costs can be substantial, and securing funding can often be a really important if not necessary component in a publisher’s decision about whether or not to publish an international title, so the fact that many countries around the world offer translation grants to help cover these costs is hugely helpful. However, it’s not straightforward, in that publishers need a much longer lead time for publication than usual if they are to rely on external funding since the application process is often lengthy and not guaranteed. The type of contracts a UK publisher signs with an international publishing house may also have to build in a contingency clause that states that the deal can only go ahead subject to funding, and this provides some uncertainty.

In terms of additional obstacles, one that is often raised is a reticence on the part of book buyers to take a chance on a translated title that may not reflect their lives or experiences, leading to fewer book sales. This, if you remember, was also the argument against publishing ‘diverse books’ – that they would only cater for a niche market – which I hope most people would agree has been largely discredited. The only thing I would say is that a careful balance does need to be made when you’re dealing with books for the youngest of children who do need some element of recognisable context in which to anchor a story.

Another obstacle often raised is that authors and illustrators living in other countries can’t help drive sales in one’s own since they’ll have no presence at book fairs, school visits, library events etc. While this is true to some extent, there is now a lot that can be done virtually, thanks in some degree to the pandemic, and authors can often make their presence known via social media very effectively. For Lantana in particular, we have authors living all around the world so we’re used to dealing with authors in absentia!

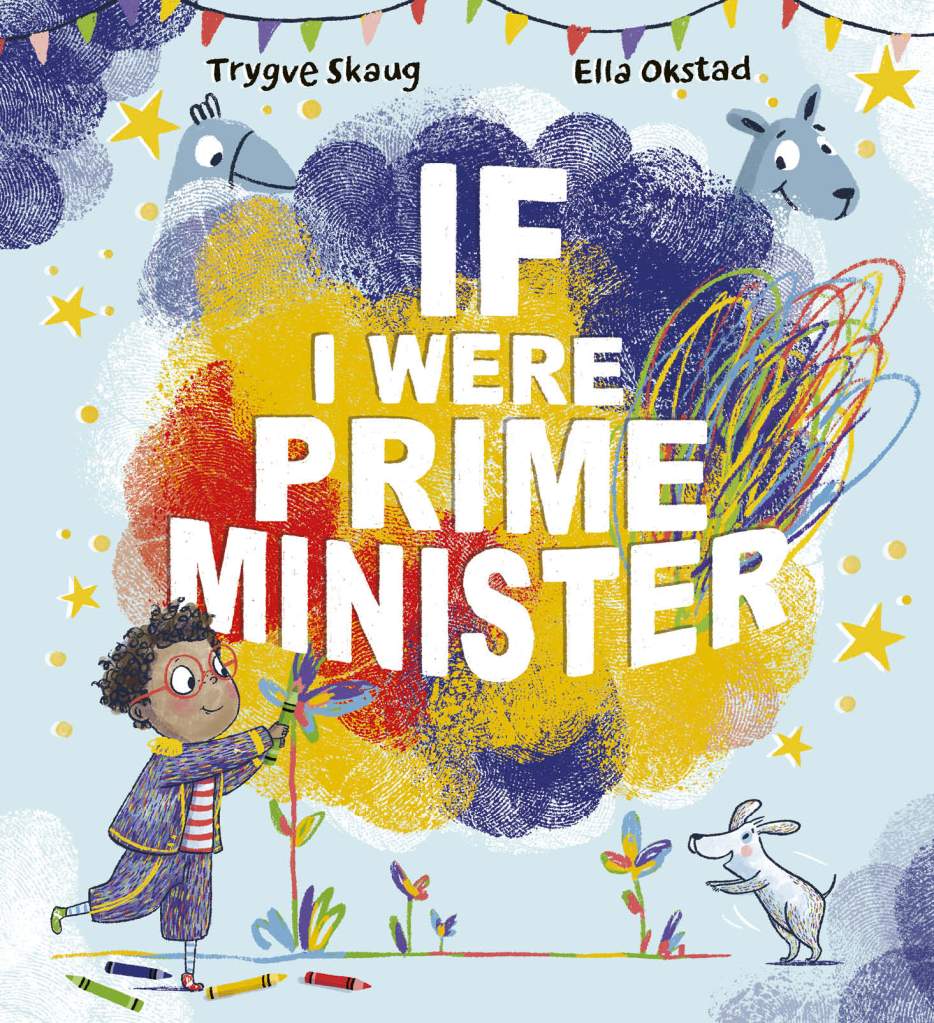

Literary festivals can also provide funding, as the Cheltenham Literature Festival is kindly doing to bring the Norwegian author and illustrator of our picture book If I Were Prime Minister, Trygve Skaug and Ella Okstad, over in the Autumn.

Finally – if you’ll forgive the very long answer to this question! – I would personally like to suggest that the greatest obstacle to translating more titles in the UK is a lack of language proficiency in most British publishers. As a publisher, I’m uncomfortable with allowing anyone other than myself and my immediate team to make a decision on which books to include in our small and selective list, but with only a smattering of French and Spanish, I’m unable to read more than the most basic of picture books in these languages for myself. It’s no surprise to me that publishers on the continent often build lists in which half of their titles are translated since they are likely to speak several languages between them. There are some ways to overcome this barrier – consulting ‘best of’ lists like the White Ravens, looking at winners of international prizes, and paying for translation samples, although this is costly – but the fact remains that publishers over here need to lose a little bit of control in the process if they’re to include translations in their lists, and publishers tend not to be very good at this – at least I’m not!

CG: That’s such an interesting point that I hadn’t thought about! Thank you so much for answering this and all my other questions in such detail. To end, is there anything exciting you have in the pipeline that you’d like to share with our readers?

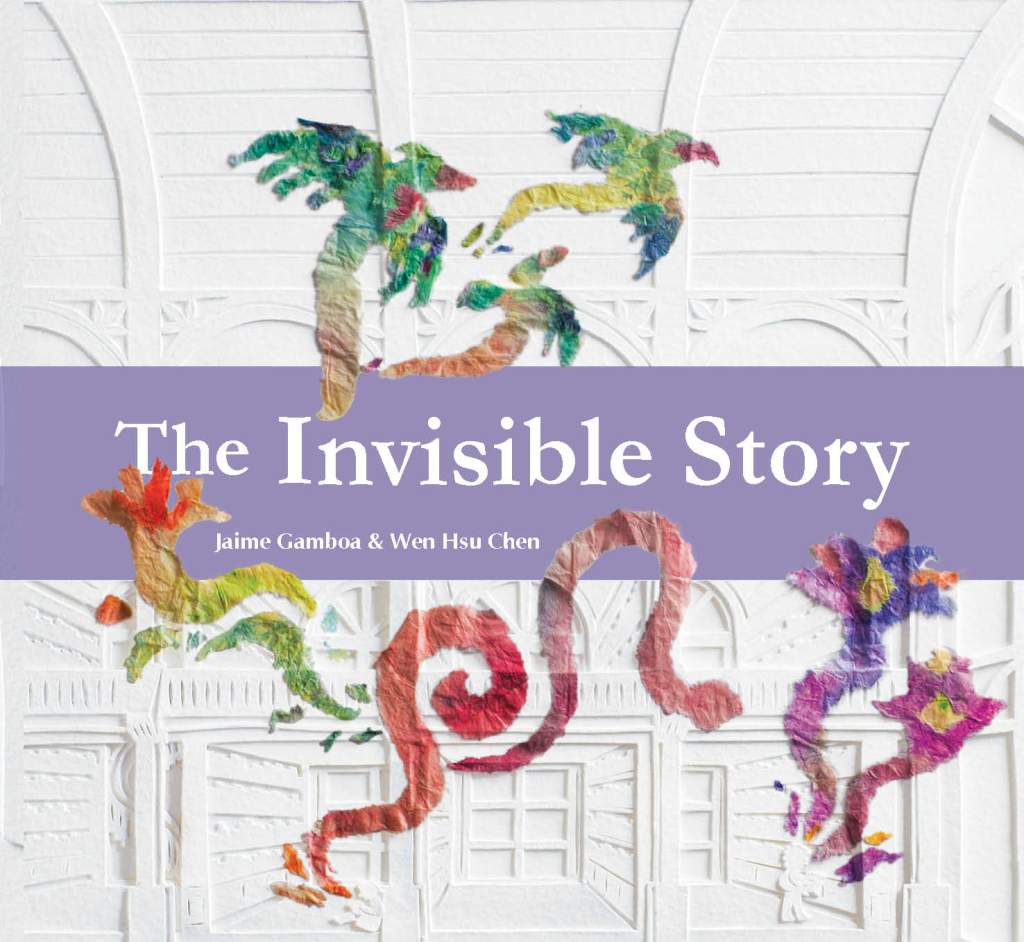

AC: Looking ahead to Spring next year, we’re excited to be publishing The Invisible Story by Mexican author Jaime Gamboa and Mexican Chinese illustrator Wen Hsu Chen, translated by Daniel Hahn. This beautifully quirky picture book, told from the perspective of a book on a library shelf, was originally published in Uruguay by publishing house Amanuense. We first discovered the book thanks to the translation-focused Reading the Way project organised by Outside In World several years ago and are delighted to now bring it to English-language readers. Envying the other books in the library with their shining letters and colourful pictures, the invisible story believes its pages to be blank. It is only when a young blind girl enters the library and runs her fingertips over the book’s white pages that the invisible story learns of the wonderful stories it contains. This unusual book gently explores the braille reading system, and we are excited to be working with the RNIB to make an accessible version of this book available to visually impaired readers.

CG: Well we’ll certainly look out for that, that sounds fantastic! Thank you so much for talking to us today. It’s been a pleasure and we wish you the best of luck for all future projects.

*Find out more about the Reflecting Realities research by the Centre for Literacy in Primary Education (CLPE) and download the latest report

Alice Curry is the 2017 winner of the Kim Scott Walwyn Prize for women in publishing, a former academic lecturer and the Founder of Lantana Publishing.

Charlotte is a Spanish to English translator who works as a Rights Assistant at Nosy Crow, an independent children’s publishing company. She adores children’s literature and the way in which children’s literature translation can aid children’s development and nourish creativity.