By Amanda Bird

While multiple themes link this Eerdmans quartet, two predominate: the sea and human encounters. All four titles adhere to realism, in the main; facts particularly abound in Fadeeva’s guides to the science of wind and water. But her conceptual illustrations spill from the page, and the unlikely encounters in the two fiction titles encourage us to believe in the power and possibility of human connection, even when circumstance and geography divide us.

Three of these titles also share a common source language (Russian) and translator (Lena Traer), while Here and There was published simultaneously in Chinese and English. All four volumes were created by gifted author-illustrators with complementary sensibilities; in each volume the joy of discovery rewards attentive observation.

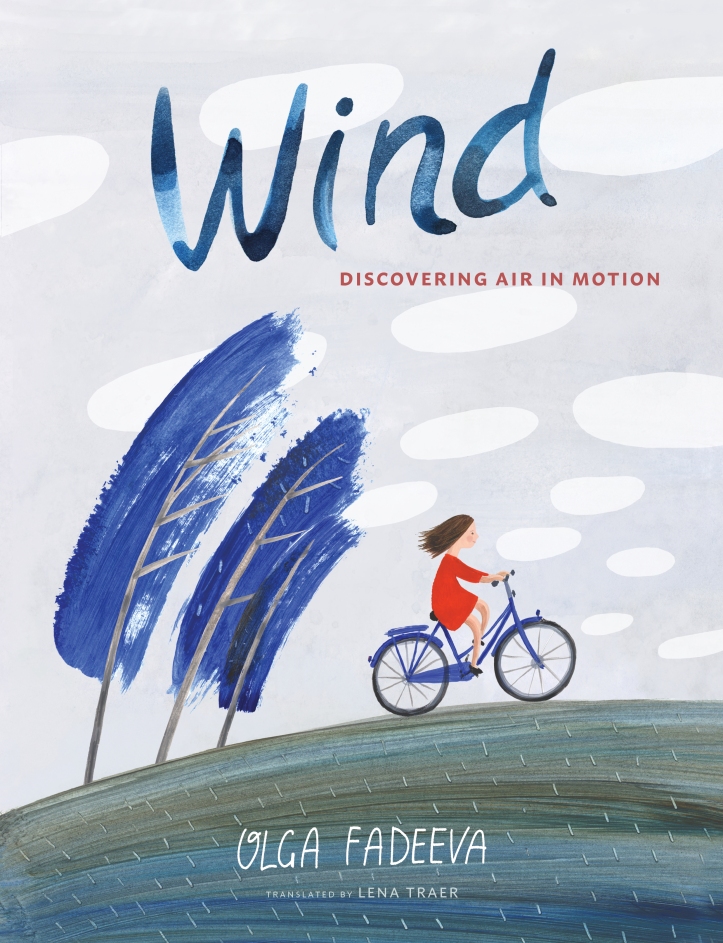

Wind: Discovering Air in Motion

Written & Illustrated by Olga Fadeeva

Translated by Lena Traer

Translated from Russian [Belarus & Russia]

Published by Eerdmans Books for Young Readers (2023)

With vivid illustrations in a wide-ranging palette, Wind is a felicitous marriage of science and art. Fadeeva introduces official terminology for the patterns of global air movements and describes major influences: Earth’s rotation, distance from the equator, land formations, ocean currents.

She also demonstrates how wind has interacted with human history and culture. The rise of trading goods led to ship building, which expanded over centuries, as sails evolved and advanced sailors’ capacity to navigate. Elsewhere Fadeeva describes the uses of kite flying, means of harnessing wind power, and technologies for measuring it.

Not typically drawn to science myself, I found Fadeeva’s volume—forty-eight detailed pages, rated for ages seven to eleven—highly engaging, with its multitude of fascinating facts. Did you know that wind can carry sand from the Sahara across the Atlantic to North America? Or that wind-pollinated trees often bear blossoms muted in scent and color because they don’t need to attract bees?

Fadeeva’s bold strokes, by turns impressionistic and representative, reflect the power of this natural phenomenon.

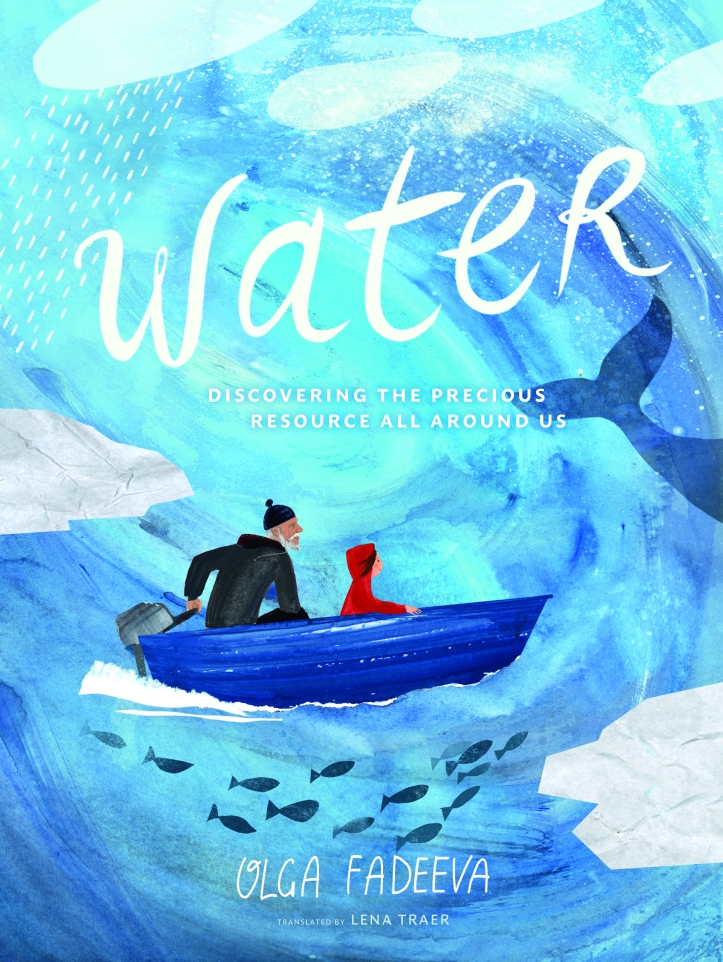

Water: Discovering the Precious Resources All Around Us

Written & Illustrated by Olga Fadeeva,

Translated by Lena Traer

Translated from Russian [Belarus & Russia]

Published by Eerdmans Books for Young Readers, 2024

Fadeeva delivers another immersive compendium of facts, this time on water and everything associated with it: seas, oceans, currents, tides, and things that move and dwell in, on, and beside the water. At fifty-six pages, gauged for ages eight to fourteen, it is most readily absorbed bit by bit.

Readers dipping into the section on seas will learn that more than size sets them apart from oceans. Even though the Sargasso Sea, for example, is bounded on all sides by the Atlantic, its average surface height is one meter higher than the surrounding ocean.

The water cycle naturally receives attention, as well as underground reservoirs and historical systems for delivering water. Fadeeva elucidates rainbows, salinity, flooding, and glaciers. Even deserts merit attention, as regions low in water. Another spread presents ancient gods associated with the oceans, alongside the technologies that have helped elucidate their mysteries.

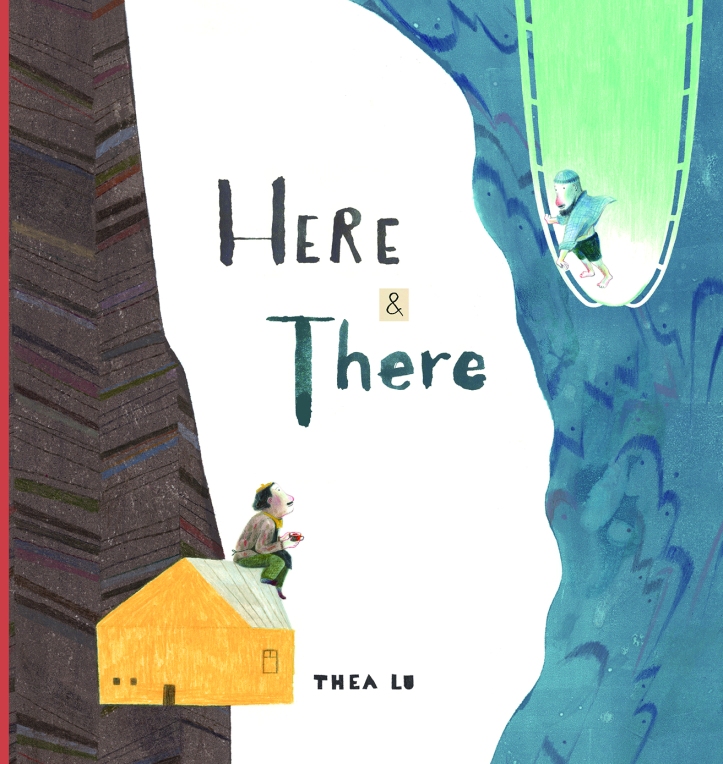

Written & Illustrated by Thea Lu.

Translated by Thea Lu

Translated from Chinese [China]

Published by Eerdmans Books for Young Readers (2024)

In gentle color and text, Lu contrasts the lives of two men. Dan runs a seaside café and has never traveled; Aki has spent his whole life aboard a sailing vessel. Both have their routines. Both engage with people: The world comes to Dan in his cafe, and Aki is welcomed wherever he goes. But both feel disconnected from time to time. Dan feels isolated, Aki rootless.

Lu portrays Dan’s story in the warm tones of earth and wood, Aki’s in the cool blues of sea and sky—until the day the two men meet, and the colors mingle. A final foldout makes tangible the parallel nature of their lives, intersecting in one fleeting encounter. Muted hues match the subdued nature of the story; no rising action leads to a grand climax. Indeed, we discover at length that the fateful encounter is already in the past. But Lu’s artful book celebrates the leading and coming together of disparate modes of life.

Written by Anna Desnitskaya

Translated by Lena Traer

Translated from Russian [Russia]

Published by Eerdmans Books for Young Readers (2023)

Like Here & There, Desnitskaya’s creation employs innovative (though not unprecedented) design toportray two far-flung characters. Vera lives on Russia’s Kamchatka Peninsula and Lucas on the coast of Chile. Lucas’s story reads from one direction; for Vera’s, the reader must turn the book over and read from the other direction. On one cover, Lucas stands waving out to sea, surrounded by cacti. On the other, Vera, in similar pose, is framed by grassy hills and silhouettes of wildflowers.

The two young people report in first-person, “this-is-my-life,” school assignment style: their home, family, favorite things, treasured possessions, life goals, routines, pastimes, pets, and friends. Incidentally, neither has many of the latter. In a clever twist, each has an imaginary companion that looks remarkably like the other.

Both Lucas and Vera like to wander down to the shore at night with a parent and flash Morse code out to sea. Their stories meet in the middle, when the children’s flashlight beams, impossibly but charmingly, intersect in three text-free spreads. At the very least, the assertion makes us reconsider what we’ve read: Could it be possible? Previous mention of works by C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien has already introduced the fantastical. We want to believe that longing to find a friend makes it happen; maybe someday they will meet.

The role of language and translation, if not prominent, is at least distinctive in each of these books. In On the Edge of the World, Lucas and Vera each speak a language different from readers of the English-language edition, and they use yet a third mode to communicate—Morse code. My brief investigation of Morse revealed that while it was developed for English, it has since been adapted for other languages. For the purposes of the story, we can presume Lucas and Vera use English, or that it’s a minor detail that doesn’t bear lengthy consideration.

In Wind and Water, the publisher’s thanks to a science educator acknowledges one of the challenges of translation—dealing with official terminology. In another sense, however, pinning down a specific scientific term could be easier than capturing the essence of a specialized or fabricated word. As when Vera describes how her mother teaches her to make a secret place in the ground to store her treasures. Traer opts for transliteration, sekretik being serendipitously close to “secret.”

In Here & There we must assume Dan and Aki speak different languages, as must many of their international acquaintances. If language barriers arise, we are not told of them. Interestingly and no doubt intentionally, no identifying notes appear on Aki’s scrapbooked photos. And only two of Dan’s mementos bear legible words. A partially obscured title reads “—Map.” And scrawled across the top of a piece of music (itself a form of notation), apparently written by one of Aki’s guests is, “wonderful people.”

In an interview, Fadeeva said the girl and grandfather who recur in the illustrations of Wind and Water represent her and her grandfather, who was a sailor. They constitute yet another commonality with On the Edge of the World (where both Lucas and Vera mention their grandmothers) and the sailor Aki in Here & There. The intercontinental and intergenerational elements of all these books demonstrate the timelessness of both scientific phenomena and essential human connection.

Amanda Bird is a freelance writer and editor living outside Eugene, Oregon, with her husband, teen daughter, and various international housemates. Her work in progress is a historical novel set in 1908 Tajikistan.